I visited Athens late last spring, just before Greece’s near-default on its debt and possible exit from the euro. At the time, the city exhibited no signs of near-collapse to the untrained eye (mine): The subways were running well, the Acropolis was open and packed, the restaurants and bars we frequented at night were buzzing. Underneath the surface proficiency, though, I began to notice a certain faltering in Athens’ fabric. For example: In 2015, there was no centralized online location to purchase boat tickets to the Greek Isles, even though boat tickets to the Greek Isles are a critical cog in the wheel that keeps the tourism industry there churning. In ways like this, in Athens it can be excruciating to get basic errands accomplished.

The dysfunction, instead of beating them down, had inspired a twisted, reactionary vanity in its residents. They doubled down on their pride. They displayed complete equanimity in explaining to us why we couldn’t ship a bottle of wine home, or book a boat without taking a cab to a travel agency (this at a luxury-class hotel, where you’d think the concierge would be able to push a few buttons to make it happen.)

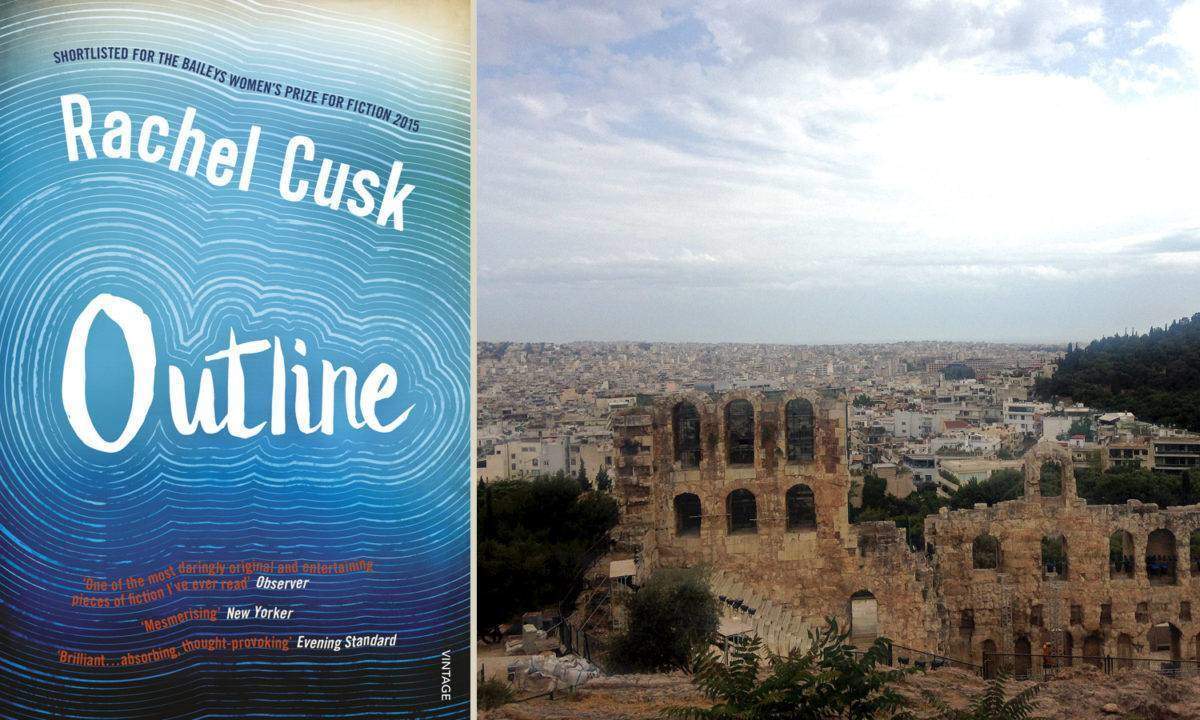

There’s none of this to be found in Rachel Cusk’s 2015 novel, Outline, which recently brought in a slew of year-end best-of awards and is set mostly in Athens. It is instead very much a novel about visitors to Athens. A reader with an interest in the country of Greece would need to accept this before finding what’s worth reading here. The city serves as the backdrop, but any city could have served as the backdrop without changing this novel in any substantive way.

For people who want to prove that a novel can work without a standard story arch, here is their book. In place of plot, there is a vague premise: A woman flies to Athens to teach in a writing workshop. On the plane over, she sits next to an older Greek man with whom she strikes up such a confessional conversation–failed marriages, failed careers, failed parenthood–that it would be impossible for them to part ways without promising to keep in touch.

This kind of frank, analytical, inward-looking verbiage is the foundation of the novel. From one scene to the next, I was left thinking how nobody really talks like this, and every so often annoyance at this fact began to well in this reader. But I got past it, and with the exception of some of the self-serious ramblings of the narrator’s students, fully engaged with the myriad characters’ introspections. Despite the plotlessness and the nebulousness, this book is eminently readable, and in the end, very good.

If there is a theme the bonds each scene, it is the unpacking of low-grade unhappiness. Not a single character seems contented. Maybe that’s because they can’t stop overthinking everything. Or maybe it’s that low-grade unhappiness is universal in the human condition, and these are a series of humans we are encountering.

The reader isn’t given to know much about the author, although it emerges that she too floats along in want of contentment and struggles with a low-grade unhappiness. She’s a writer who lives in London. She has children and she is single. We don’t know where in London or how many children or who their father is. We’re not that curious to find out. She’s not that eager to tell us: “I have come to believe more and more in the virtues of passivity, and of living a life as unmarked by self-will as possible,” she writes.

Once in Athens, the narrator stays in the apartment of a stranger who likes to offer her apartment up to visiting writers. She workshop she teaches involves each student going on and on about some small event in his or her life, deconstructing it and probing it for meaning in a way that people rarely do out loud. They strive to give metaphysical weight to small anecdotes from their recent lives, an overheard familiar piece of music that brought back a sense of loss, a discovery of an abandoned handbag in a city square, etc etc.

Outside of the classroom, the narrator goes to dinner with people of a similar proclivity. One colleague, Ryan, muses about his failure to make time to write anymore. He wants to get into the right headspace again, but he hasn’t. “When you’re in that place you make time for it, don’t you,” he says, “the way people make time to have affairs. I mean, you never hear someone say they wanted to have an affair but they couldn’t find the time, do you?” Another dinner companion says of a character in one of her books, “She is experiencing a crisis of femininity that is also a creative crisis, yet she has always sought to separate the two things in the belief that they were mutually exclusive.”

An old friend from London observes that “in his marriage…the principle of progress was always at work, in the acquiring of houses, possessions, cars, the drive toward higher social status, more travel, a wider circle of friends, even the production of children felt like an obligatory calling-point on the mad journey.”

It’s passages like these that elevate Outline to near-greatness. It’s not the story. There is no story.

The closest thing to a plot point comes the second time the narrator goes on the boat of the Greek man she sat next to on the flight over. He is equally full of pithiness. “[S]uccess takes you away from what you know, while failure condemns you to it,” is one of the things he says out loud. He also, spoiler alert, tries to kiss her. It is, though, of course, inevitably, another nonevent in this woman’s life.

Get Rachel Cusk’s Outline on Amazon.

-by Sarah Stodola