Bolivia, a landlocked country of diverse terrain, has averaged 4.8 percent growth in the last few years, according to the World Bank. Things are happening here, but much of this South American country remains largely undiscovered–particularly when it comes to food, even though few places on earth boast such a varied offering of edible items.

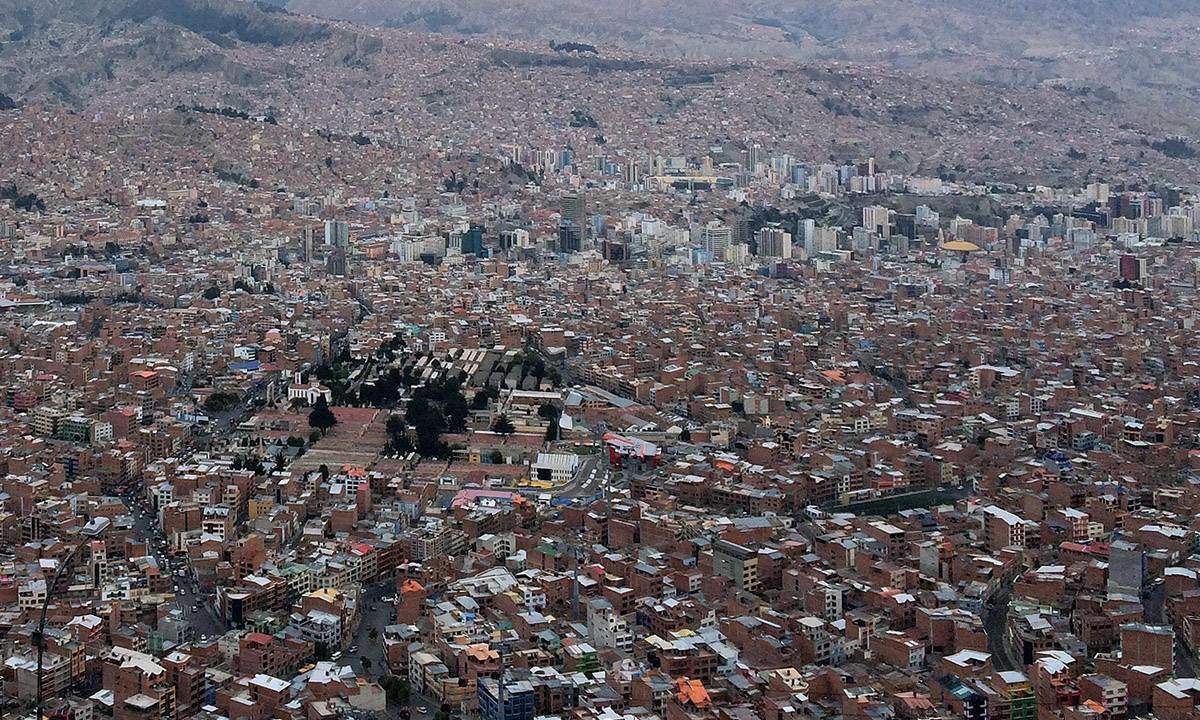

The source of the country’s gastronomic intrigue is centered in La Paz, the country’s capital and a city almost above the clouds. The pull can be mysterious. Perhaps the altitude, a cool 13,313 feet above sea level, adjusts the taste buds, or maybe it’s residents’ obsession with all things local. Whatever it is, everything tastes good here. Really good.

Nowhere in the city is this truer than at Gustu, the Bolivian restaurant in La Paz’s tony south side opened by the guys responsible for Copenhagen’s world-renowned locavore temple, Noma. Since Gusto opened in 2013, the team behind it has been quietly revolutionizing Bolivian cuisine, from the highest end to its street food. I was lucky enough to spend a few days recently feasting my way through La Paz, including at Gusto (twice). I was in love.

Claus Meyer, part money and part brains at Noma, chose Bolivia largely because it’s a country whose natural culinary offerings have gone underutilized. To capitalize on this and to build on the Noma phenomenon, he wanted someone at the helm with Danish roots but some South American experience. That led him to Kamilla Seidler, A Danish chef who has worked in some of the world’s best restaurants, for the role in La Paz.

For Seidler, the move to Bolivia for such a restaurant had a lot to recommend it. “It’s the biodiversity, the politics, the people, the economy—Bolivia just made sense from every perspective,” she says.

The staples of Bolivian food may be corn, potatoes and beans but you’d be wise to hold off on presumptions of blandness. There are, after all, thousands of varieties of potato to be found here, each with a distinct experience to offer the palate. Bolivian cuisine as embodied by Gustu is not about reinterpreting “grandma” dishes, but about finding the most extraordinary local ingredients available in some of the most remote parts of the world, as well as right in the city of La Paz. Seidler says, “We see it like this: if we find an amazing potato we will use it just like that, and let it speak for itself.” In Denmark, Noma fueled a total culinary revolution with leeks and some cauliflower. In Bolivia, a potato can have the same transformative powers.

Gustu works 100 percent with Bolivian products, from the vegetables to the meat to the coffee to the wine. “It would have been absurd not to work with everything we have right around us,” said Seidler. “We don’t need to import a strange, weird fruit from Asia—we have that strange, weird fruit right here in Bolivia.”

In her work for Gusto, Seidler is out the kitchen as much as she’s in it, managing the social ambitions of the business, which are in fact the main thrust of the overall project and include a school, a restaurant, a logistics company, a delicacy outlet (named Q’atu, launching soon), and a hotel under construction for opening later in 2016.

The school program, in the neighboring city of El Alto, currently enrolls roughly 650 students learning how to cook and to spread the techniques of healthier eating through their families and communities. Many of them cut their teeth at Gusto. “We decided what we wanted to do is have a casual fine dining restaurant but all run by students—so to speak—with managers of course supervising,” said Seidler.

The company also runs a project called Suma Phayata (“well cooked”), focused on the production of street food in La Paz and teaching vendors about hygiene basics and techniques for running a more efficient shop; all to inspire more gastronomic tourists to come explore Bolivia.

Street food in La Paz is all about the time of day: for breakfast, saltenas (a Bolivian empanada) and humintas (the local version of tamales); afternoons are for Bolivian pork sandwiches made with local pickles and chilies and a batido (milkshake) to drink. Any time of the day is good for anticucho (flame grilled beef heart served with potato and peanut sauce), rotisserie chicken, and quinoa soup done a million ways. “It’s tradition to eat like this—it won’t change, it’s just the way it’s done,” said Seidler. Some of the ladies in the street food markets have been selling the same sandwich, made the same way, for over 50 years–testament to the quality of the product. Gusto wants to help make it even better, and more accessible.

I asked Seidler what the next big thing in food will be globally, she not surprisingly referenced a South American treasure. The Amazon, she says. “People think the Amazon is just a green spot but it has so much potential from fish to wild meats to all the crazy plants,” says Seidler. “The Amazon, with all its mystery, can be sustainability harvested and thus improve the lives of indigenous people and bring awareness to the real fight–protecting the lungs of the world.”

Environmentalists and cooks can get together and agree on this. And perhaps the highs and lows of a new Bolivian cuisine can assist.

-by Daniel Scheffler