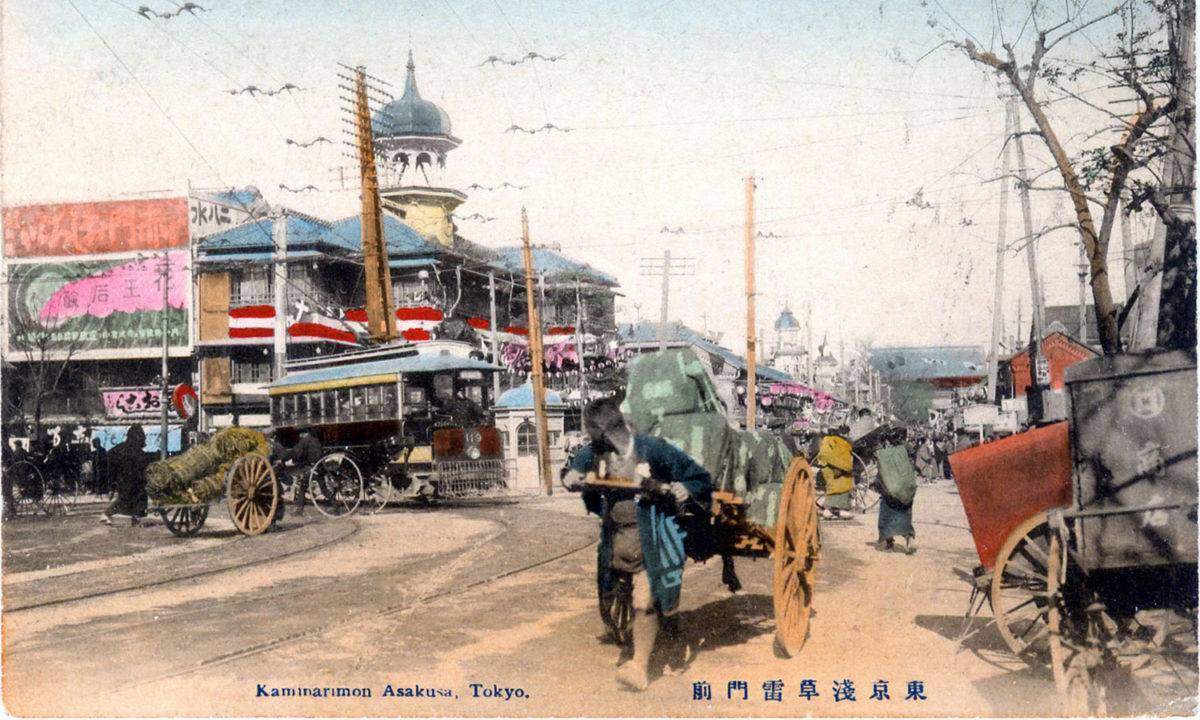

Walking along Hisago Dori, a covered street in Tokyo’s Asakusa neighborhood festooned with paper lanterns and ribbed with red pillars, a friend and I were looking in the shop windows at the piles of mochi (rice cake), the ranks of plastic sushi, at the kimonos and the yukatas. I had lived in Asakusa for about six months and had just about got the hang of street etiquette, the pedestrians, cyclists and rickshaws that moved around the areas that bordered Sensōji Temple.

The Sensōji pedestrians came in various groups: dawdling tourists, gambolling office ladies, drunken salarymen. The tourists would stop abruptly to take photos of the historic area, causing me to swerve out of their way, hard to do sometimes in flip-flops. The office ladies always seemed to be giggling while they pranced, hands over teeth that resembled earthquake-stricken graveyards. The salarymen lurched, their bellies full of beer and noodles, pissing in the streets; again, not great for flip-flop wearers. Tokyo pedestrians do not move at the same rate as a Londoner or New Yorker. They amble, they practice what I called “wandering diagonalism,” straight lines were anathema to them, corners a problem, yet they never seemed to bump into one another—even through the crush of the shopping districts, or the rhythmic suck and flush of humanity on the Shibuya Crossing.

The rickshaws carried tourists of every nation. Once, on a humid monsoon afternoon, I saw a smartly dressed Japanese woman and her partner sitting patiently in a rickshaw, the man wearing a full giant-panda costume. These gondolas of the streets are pulled by fit young students dressed in traditional costume, on their heads either a kasa (conical hat) or a hachimaki scarf to absorb the sweat of their labors. I walked through the temple complex every day, empty in winter, nearly impassable in the spring and summer months, through snow, rain, wind and unbearable heat and had no problem with the pedestrians or the rickshaw bearers. But I did have trouble with the cyclists.

Let me clarify that.

Asakusa is the Amsterdam of Tokyo. There are more cyclists in Asakusa, especially around Sensōji, than anywhere else in the metropolis. They cycle through the pedestrian complex to the various train stations and the bike parks and they cycle along the Sumida River and over its bridges. The majority of them are careful, polite and aware. But I did have trouble with a certain type of cyclist. The old-woman cyclist. The old-woman cyclist with front basket full of either shopping or one, two, three or more small dogs, usually long-haired dachshunds. The old-woman cyclist with front basket full of either shopping or one, two, three or more small dogs, usually long-haired dachshunds, carrying an unfurled umbrella against the rain or brightly painted parasol against the sun. The old-woman cyclist with front basket full of either shopping or one, two, three or more small dogs, usually long-haired dachshunds, carrying an unfurled umbrella against the rain or brightly painted parasol against the sun, talking into her cell phone clasped between shoulder and ivory cheek. The old-woman cyclist with front basket full of either shopping or one, two, three or more small dogs, usually long-haired dachshunds, carrying an unfurled umbrella against the rain or brightly painted parasol against the sun, talking into her cell phone clasped between shoulder and ivory cheek, while trying to steer and balance on her bicycle.

![Sensoji Temple. Photo by Kakidai (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://flungmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Sensoji_at_night_Tokyo2-1024x614.jpg)

![Sensoji Temple. Photo by Kakidai (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://flungmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Sensoji_at_night_Tokyo2-1024x614.jpg)

![Sensoji Temple. Photo by Kakidai (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://flungmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Sensoji_at_night_Tokyo2-1024x614.jpg)

On that day, while walking with a friend along Hisago Dori to one of the workers’ noodle shops at the end of the covered street, I saw one of these old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machines weaving among the pedestrians, unsteady, front wheel rocking-and-rolling, moving impossibly slowly, yet inexorably in our direction.

A few weeks before on a nearly empty backstreet of Omotesando, another of these old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machines turned a corner, saw me and, head-down, came upon me resolute and steadfast. I jumped out of the way, up on to a small wall, but not before her front wheel went across my big toe. I swore at her in English and she ploughed on, parasol a-wobbling, dogs a-yapping. I looked down at my foot, blood-spurted under the nail of my big toe, making my flip-flops even more soggy and treacherous to control.

And that day, walking along Hisago Dori on the way to one of the workers’ noodle shops with my newly arrived friend, we faced another of these mothers of menace, these sisters of perpetual vacillation. And I moved one way while my friend moved another and this seemed to confuse the old woman even more because she veered towards me and then towards my friend and the people walking between us were invisible to her as if our otherness drew her old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machine towards us like a fluctuant tractor-beam. And then, as if finally locked on its trajectory, the old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machine moved unhurriedly and implacably into the groin of my friend, leaving him in a heap on the floor, clutching his genitals.

The old woman stopped for a second, looked into the distance, then put her foot down, steadied herself and propelled off towards the traffic of Kototoi Dori, slightly wobbly, dogs a-shiver, parasol a-rattling. My friend was fine, a little sore, a little shocked, a lot amused. We sat outside the workers’ noodle bar, had an ice-cold beer and slurped at our ramen. But forget the tattooed Yakuza, forget the nationalists and their noisy sound trucks, forget the Thunder Gate and its quartet of fearsome gods, forget even the old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machine for there is another more terrifying species that haunt the urban areas of Japan.

Although diminutive, they are armed with sharp tanto-like elbows, shielded with wire shopping baskets and trolleys, armoured in polyester twinsets, helmeted in primary-colour rain or sunhats, they fix their enemies and prey with a soul-shuddering stare, a dark eye that has seen it all—monsoons and earthquakes, bombs and firestorms—they are the scourge of all other would-be happy shoppers. Yes, look upon them, they are the dragon ladies of the grocery store. Tremor and behold!

I like to cook. I would say my specialty was curry. Back in my student days, my girlfriend—whose parents were Punjabi—taught me how to cook butter chicken, tandoori chicken and various vegetarian side dishes. She showed me the different mixtures of spices and herbs, how to cook rice properly and how to heat naans and rotis. Because of our financial situation we replaced the chicken with eggs and the meals would last us all week. Since then, I have become quite a good cook, experimenting with mainly Eastern dishes, sometimes quite successfully—you should try my watermelon curry.

So, while in Tokyo, I enjoyed trying to copy Japanese dishes I’d eaten in restaurants, mostly noodle recipes with tuna or chicken, prawns or scallops or a mixture of all these, throwing in nori (seaweed) and goya (bitter gourd), fuki (bog rhubarb) and kabocha (squash) with various miso pastes. I even liked natto, the pungent fermented soybeans our Japanese friends insisted we eat and yet turned away in disgust when I offered them Marmite. And then there were the mushrooms—the slim and pale-gold bunches of enokitake, the phallic woodwind-like eringi, the USS-Enterprise-shaped hiratake and the comical shiitake. All would make their way into my stews.

My girlfriend at the time worked six days a week and—when I was not exploring Tokyo on foot or sitting at my desk writing or fighting with my monster half-Japanese wildcat tabby or sitting on the balcony reading and drinking beer—I was either cooking or shopping for ingredients with which to cook. This meant going to one of two supermarkets, the Sanpei fresh food market on Kokusai Dori or Ozeki supermarket on Kaminarimon Dori. Either meant a hazardous walk dodging the old-woman-bicycle-umbrella-dog-phone-monster-machines, but a trip to Ozeki meant a walk along the Nakamise with its tiny old stores selling clogs and chopsticks, fans and paper, kimonos and yukatas, film posters and samurai swords. And even though the Sanpei had wider aisles and tended to be less busy, I preferred Ozeki, with its outdoor fruit and vegetable stalls.

So most days, I would head off through the Sensōji complex, past the Shinto Asakusa Shrine, the Buddhist Sensō-Kannon Temple, past the five-storied pagoda, the ponds full of koi, through the Hozomon with its giant straw sandals, down the Nakamise, squeezing past the tourists, towards the Kaminarimon and its monstrous dragon-sealed alien egg—the chōchin (lantern).

I am an impulse shopper, so whatever looks interesting on the day is what I will buy. I usually start with protein, fish, meat or seafood and then add vegetables, different rices or noodles, more spices, herbs and sauces to add to my collection. But entering Ozeki was like entering the dohyō and, instead of sumo wrestlers, I went into battle with the old ladies who haunted the supermarket. I encountered these old ladies in other stores in other parts of Japan but it seemed the old-ladies-with-tantō-sharp-elbows and battering-ram shopping baskets who patrolled Ozeki were meaner and faster, braver and bolder, more tactically astute than their counterparts elsewhere. Maybe it was because the aisles were narrower, the bends sharper, the fish fresher, the meat leaner, the octopus plumper, the roe shinier, or maybe earlier that morning, while sipping their miso, they had been reading Sun Tzu’s Art of War or were carrying Carl von Clausewitz’s On War in the depths of their shopping bags.

These were 21st-century onna-bugeisha, female samurai who ruled the aisles as if they were the alleyways of ancient Edo, and their own form of bushido—“the way of the warrior”—meant that their rules were theirs only, no younger person, male or female, Japanese of gaijin, would stand in their way. I learned to back off and observed the righteousness with which they went for the rice cakes, the courage they showed gathering the konbu (kelp), their benevolence and respect for no one, their sincerity in their search for sashimi, their honour in hunting down USS-Enterprise-shaped hiratake, their loyalty to lotus root and voodoo lily, their self-control in not impaling me with their tantō-sharp elbows as they ambushed the amanatsu (large hybrid oranges), skirmished for the sudachi (like limes) and blitzkrieged the budos (grapes). I would wait until they had finished, their battering-ram baskets heaving with plunder, their tantō-sharp elbows—for now—safe within their polyester sayas (sheaths) and I would collect my proteins and my vegetables and my noodles and my condiments and I would wait in line behind the old ladies until it was my turn at the check-out till.

And I would follow them out of Ozeki and watch them pass the flower stalls, where they would squeeze their shopping bags into a wicker basket already stuffed with one, two or three long-haired dachshunds. They would unfurl their umbrellas, take out their cell phones and mount their bicycles. And I would quickly cross the road, walk past the Thunder Gate with its distended and blood-coloured mono-orchid lantern and rush into my favorite pub, the Kamiya Bar, for a swift beer or six.