At the tail end of a vacation in France a few years ago, my boyfriend and I had a couple days in our rental car to get back to Paris from Bordeaux, where we’d been enjoying the countryside and the ocean and the wine and the perfectly ripe avocados. We had no plan, just a general direction we needed to pursue, waiting along the way for something to pique our interest enough to stop. I remember whirring past windmills and fields of sunflowers, and then I remember passing a large building emblazoned with the logo of Courvoisier, a cognac so well known that even I knew about it. And then we saw signs for the town of Cognac.

It hit me then that of course there’s a place called Cognac and that, like so many French things, the place is synonymous with the thing it produces, as it is with Champagne, Dijon, Camembert, and so on. The thing, in this case, was a storied brandy. We exited the freeway.

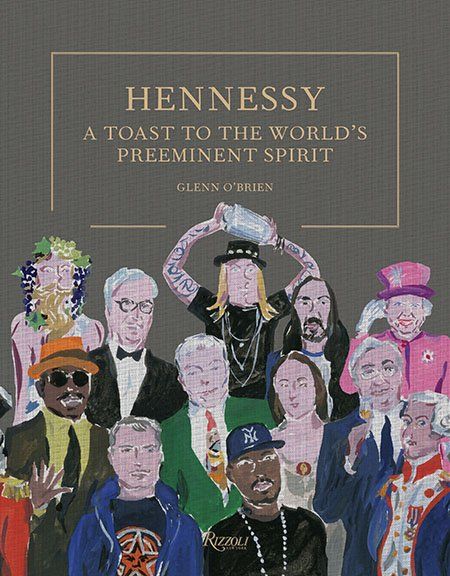

by Glenn O’Brien

Illustrations by Jean-Philippe Delhomme

Hardcover. 239 pages. Rizzoli.

$55

Cognac, we discovered, is a perfect midsized French town, with pedestrian streets of limestone and leafy squares filled with café seating. Near its center, on the banks of the Charente River, Hennessy’s castle-like headquarters (and tasting room) dominate the scene.

A new book from Rizzoli Press, Hennessy: A Toast to the World’s Preeminent Spirit, commemorates the brand’s more than 250 years as a standard bearer in the world of fine spirits. The publishers enlisted Glenn O’Brien, a prominent pop culture writer, to write this history, and it’s a fascinating one, even if this version is prone at times to inflating Hennessy’s role in world historical events. To wit: O’Brien writes of the brand’s success in becoming a global company early on, “You might say that the United Nations was simply a logical progression of the ever-expanding path opened by Richard Hennessy in 1765.”

Whether or not Hennessy can claim to have served as a template for the U.N. (it can’t), the fact remains that it’s a company whose history does offer a lot that’s relevant today—immigration, globalism, and race all factor in heavily. That history began in the 16th century when winemakers were looking for a way to ship their products over long distances. Their wines didn’t keep well, so they began adding a bit of distilled wine to them, which served as a preservative. In the early 17th century, distillers discovered that if they distilled the wine twice and aged it, they had something quite palatable—brandy. Brandy from Cognac became some of the finest.

Hennessy, for all its Frenchness, turns out to be named for an Irishman. Specifically, Richard Hennessy, who fled his home country in 1745, when he was 21, and joined the French army. As O’Brien puts it, “In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Ireland was a popular place to leave,” what with the mass starvation and oppression from the Brits. While serving, Richard began sending casks of brandy back to Ireland for a small commission. Later, he settled in Cognac and began building a more formalized business around brandy. His son, James, had a knack for the business and built Hennessy into a truly imposing company. What’s interesting here is that neither Hennessy was an expert in making cognac. James’ expertise was the business of it. He was the Steve Jobs of brandy in the 18th century.

As you’d expect from Rizzoli Press, the physical book is a thing of beauty. I had a friend over while Hennessy sat on my coffee table, and she gravitated to it pretty immediately. The illustrations by Jean-Philippe Delhomme on the cover and within are great, but for me they don’t add as much to the experience as the old Hennessy advertisements reproduced throughout the book. Still, the approach has resulted in a tidy, attractive book that can be approached for casual browsing or deeper reading.

O’Brien, in addition to serving as a founding editor of SPIN Magazine and as “The Style Guy” columnist for men’s magazines such as GQ and Details, has a good amount of experience writing catalog essays for art shows. This book can be regarded as an elaborate example of such, for a brandy instead of a gallery show.

The comparison makes sense for a brand like Hennessy, which has long affiliated itself with the artists, musicians and other creatives that have shown a taste for the cognac. To its credit, this includes a longstanding affiliation with the African-American community. In one of the more interesting interviews in the book, O’Brien talks with Herb Douglas, the African-American salesman for Hennessy who in the 1960’s was responsible for lifting the brand’s popularity among black Americans, a move that would serve as a precursor to its association with rap musicians a generation later.

I wouldn’t advise looking in these pages to learn about any past controversies involving the company—if those exist, they aren’t acknowledged here. Beyond the inherent bias of a book that seems to be the brainchild of the company that is its subject, though, you’ve got a beautiful volume that’s part coffee table display piece, part well-researched history, part interview series, and part scrapbook. And for me, part souvenir of a trip I’d recommend in a heartbeat.