Until it isn’t, Katie Kitamura’s new novel, A Separation, is among the most perfect representations I’ve read in fiction of the ennui that engulfs any thinking person as she sinks, and then sinks further, into a luxury beachfront vacation. The view of the sea from the room’s balcony, the overly affectionate couple at the next table over, the “very nice pool.” None of it giving the observer any indication of which country she happens to be in.

The observer in this case is an unnamed English woman recently separated from her husband, a man named Christopher, and in the throes of deciding how ultimately to deal with that fact. For now, she has agreed to his request to keep the separation secret, even from their families.

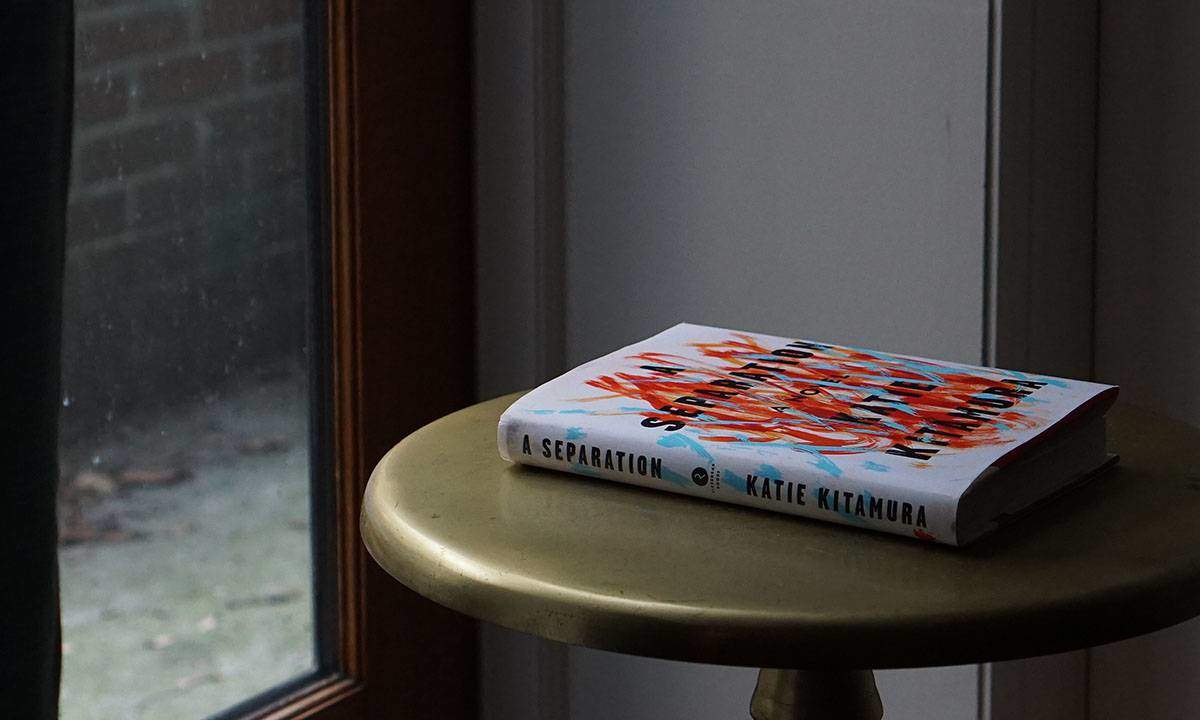

This ruse becomes complicated when, back at home in London, our observer receives a call from her mother-in-law asking after her son. She doesn’t let the woman know that she hasn’t spoken to her husband in some time, and in fact has no idea where he may be. His mother, though, knows that he is in Greece, and at her request, his estranged wife agrees travel to go there to find him. She makes her way first to Athens, then to the seaside village of Gerolimenas, a few hours’ drive to the south.

by Katie Kitamura

Hardcover, 236 pages, Riverhead Books.

When she arrives at the hotel just outside of town at which Christopher is checked in, she finds that while his belongings are in his room, no one has seen him for a few days. He’d hired a car, paid for the room in advance, and said he’d be back, the concierge informs her. And so she settles in to wait for his return. (The hotel in the novel may be based on the Kyrimai Hotel, but I can’t be sure. If so, it seems that Kitamura chose not to depict it entirely faithfully.)

On her first morning in Greece, sipping a cappuccino on the hotel terrace, she observes, “The setting here was romantic—Christopher liked luxurious accommodation, and luxury and romance were virtually synonyms for a certain class of people—and therefore made me uneasy.” Faceless luxury isn’t really her thing, at least in part because of her predilection–and it’s one I relate to–to look for the meaning behind the meaning in everything.

Just one turn of the page later, she has wandered into the nearby village and looks back at the hotel, “which had become entirely incongruous in the ten minutes it had taken to walk here. Within the grounds of the hotel you could have been anywhere, luxury was by and large anonymous…” Whereas now she’s in a verifiable place, even if she senses that she doesn’t belong there.

That her husband appreciates the inauthenticity on offer at the hotel and she doesn’t explains a lot about the state of their relationship. That inauthenticity has another role to play, as well. Fancy hotels such as this one make an enduringly compelling backdrop for plot points involving criminal transgressions—the improbable layered onto the disingenuous. And so it is with A Separation. (SPOILER AHEAD.) At the halfway point of the novel, the narrator learns that Christopher has been murdered, hit on the back of the head with a rock, robbed, and left for dead on the side of a rural road. Here, the novel as travel commentary ends and a different kind of book takes over.

Rather than heightening the suspense, the turn in the plot dampens it. I was far more interested in what might happen when Christopher finally returned to the hotel than I was with the mild whodunit and curious grieving of an estranged wife made suddenly into a widow. Still, Kitamura has a serious talent for deconstructing the less obvious motivations in human behavior. Remembering a previous time in her own life, for example, she writes, “One of the problems with happiness…is that it makes you both smug and unimaginative.”

In that case, let it be known that A Separation must be among the least happy of books.