Before I started researching a trip there last summer, the only thing I knew about Sumatra was that it produced a lot of coffee, or so I assumed after a thousand visits to third-wave coffee shops back home in Brooklyn and also Starbucks. As I poked around the internet, I learned that this Indonesian island just across the Straight of Malacca from Singapore is also a place of staggering beauty. This fact, plus its proximity to Singapore, where my fella and I would be coming from, sealed the deal. We booked the trip and looked forward to exploring remote landscapes and sipping great coffee at the source.

But sipping coffee in Sumatra, we wouldn’t learn until we got there, is not an experience analogous to eating lobster in Maine or drinking wine in France, places where the savoring of a signature product is as much a local tradition as production of it is. (The landscapes of Sumatra, on the other hand, surpassed expectations.)

We awoke our first morning of the trip on Nias, a small island off the main island of Sumatra that despite its size boasts a population in the neighborhood of 800,000. Outside of our air-conditioned cocoon, colors came at us desaturated by the sunlight already at this early hour. We took cover in the open-air main building of our little compound.

Meals were included with our stay, a necessary offering in a place with no restaurant scene. This included breakfast. But first, we said, coffee. We had a choice between Nescafe and the local beans, although both would be prepared the same way, by spooning ground coffee directly into the cup, stirring, adding some non-dairy creamer, and after allowing sufficient time for the grinds to settle, sipping.

The owner of the guesthouse said this was the Turkish style. (It was not—the beans were not ground nearly fine enough to qualify.) The Aussies staying there called it mud. I called it a lost opportunity.

We thought perhaps things would improve on the main island of Sumatra.

On Lake Toba, in the island’s northern region, we stayed in a nice reproduction Batak house owned by a Dutchman who liked to drink. He ran a professional ship, though. Even so, our morning coffee was again made the way you would make instant coffee, only with regular coffee beans. In this case, the grounds preferred to float and we continually fished them out between sips.

Aside from some glorious iced cappuccinos from The Coffee Bean at the Medan airport, this represented our coffee-drinking experience on Sumatra. To be fair, I didn’t spend any time in Medan itself, of which I’ve heard mention of an active cafe culture.

*

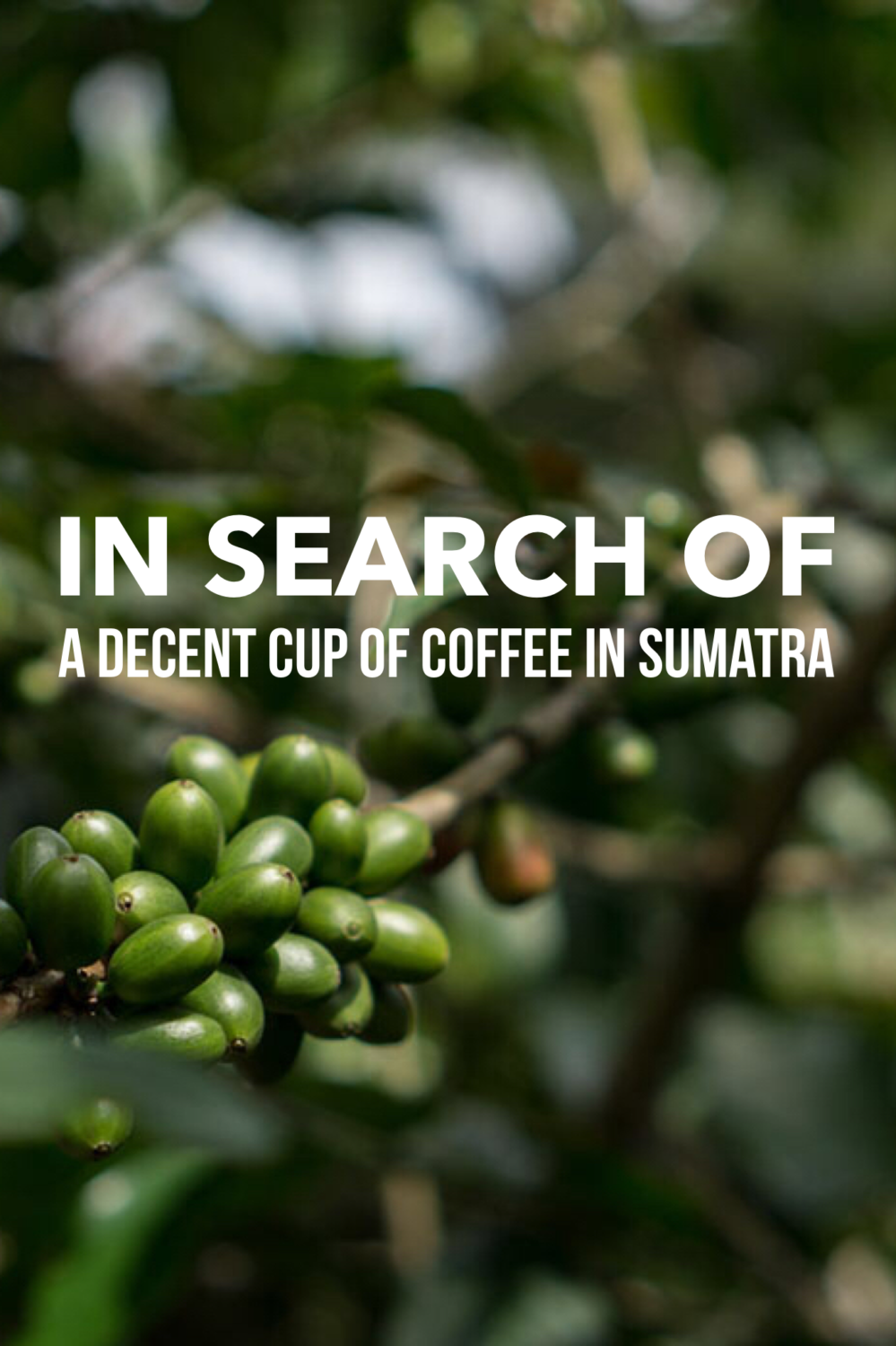

The letdown of drinking coffee in Sumatra in no way detracts from the fact that the island does indeed produce some of the world’s most renowned beans—both Arabica and Robusta, the former of which gets used for drip coffee and French presses and pour-overs, the latter of which is most often used as an espresso bean.

In the coffee snob community, Sumatran beans are controversial. Growers there use a unique technique of processing the beans while they’re wet; the added moisture produces a fuller, more intense taste that goes against current trends, which run lighter and more acidic.

Some coffee snobs, though, proclaim Sumatran coffee the best they’ve ever had. And Sumatran coffee remains among the world’s most sought after, so much so that more “Sumatran” beans are sold globally than the island could ever realistically produce. In other words, a lot of the Sumatran coffee beans out there are frauds, slapped with the designation at some point between cultivation and final point of sale in the same way that a lot of olive oil on American grocery store shelves doesn’t come from olives at all.

What surer way to taste the real thing, then, than with a trip to the source? Sumatra’s coffee seems like an obvious draw for an island that lies so close Singapore, where residents yield an impressive spending power and a strong desire to embark on weekend getaways. In Singapore, there’s a coffee shop or two for every block in the most populated areas, and it’s really good coffee, made with the best espresso machines or pour-over do-hickeys, served in spaces that could easily thrive in Brooklyn.

Sumatra, however, is figuratively a world away from Singapore. And the reason for its dearth of drinkable coffee is actually simple: Coffee growers sell their beans for export before they’re roasted. Starbucks, for example, roasts most of its beans—including those bought from Sumatran growers—at four plants in the U.S and one in Amsterdam before distributing them to their shops around the globe. Sumatra produces some of the best beans in the world, but those beans leave the island before they’re made into something drinkable. If Sumatrans want to use them to make their morning coffee, they need to import them.

On our final four-hour road trip to the airport before heading back to Singapore, I asked our driver if we’d be passing by any coffee farms. A few minutes later he pulled over at one. It was a modest affair, as all Sumatran coffee farms are. We stood at the side of the road while he found the farmer, who approached carrying a young girl on piggyback, and asked if we could take a look. The farmer had no problem with it, so we walked in. These were Robusta beans, he told us, which grow well in the relatively cool climate around the lake.

This was coffee tourism in Sumatra. And it was fascinating, but it didn’t provide me with a great cup of coffee. For that, I had to wait until we got back to Singapore.