On the last Saturday of last August, we got in a fully packed car, at the time parked in Brooklyn, and headed out. North toward Queens, then the Bronx, over the Tappan Zee Bridge to the other side of the Hudson a bit further north. We then settled into I-87, where we’d stay for the next few hours, until turning off onto the small highway toward Lake Placid. We’d done this drive before, many times, at least once a year and often twice.

That’s just the frequency necessary to instill a false sense of confidence in one’s navigation. We didn’t plug our destination into Google Maps. We bumbled along, secure in the knowledge that we were good to go until the home stretch after exit 30. We hadn’t accounted for the freeway tangle around Albany.

Somewhere around the New York state capitol, probably as we flipped through the stations for a song we liked, the freeway forked when no one was looking.

Forty-five minutes later, my boyfriend asked, “How much longer are we on here?”

“A while. We’re not even to Lake George yet,” I answered. I opened Google Maps to see where up ahead Lake George lay, and found it somewhere far to the right of the blue dot that represented our place in the universe. I didn’t believe Google Maps. The blue dot had been in the wrong place before. I closed Google Maps and reopened it.

Soon enough we began seeing signs for exits that confirmed our position. The blue dot was in its proper place. We exited what turned out to be I-90 West by Amsterdam, New York, a place I’d never heard of. We turned right over the Mohawk River and then headed back east on some highway, passing the village of Ballston Spa along the way, a place I had heard of but for which I had no point of reference. It looked prosperous, and historic. I’d have happily stopped there for a wander.

My guy and I were annoyed with both ourselves and each other, but you could feel in the car’s air pressure that we both knew it would be unreasonable to express any grievances. In the end, a six-hour drive took us eight. The result of a crime with no perpetrator, and just a couple of victims.

It hurts to say it: We got lost on our drive up from New York City to the Adirondacks. I hadn’t known that the possibility of getting lost still existed, not on this kind of trip, not in a car containing two iPhones.

I try to remember the last time, before this, that I found myself lost. Not wandering, but unintentionally and truly lost. I have to think back six years, to another car in another country. Same two people, same one driving; me, with a road map of Paris and the region around it opened on my lap. He, increasingly stressed out by my lack of conviction in reading the map.

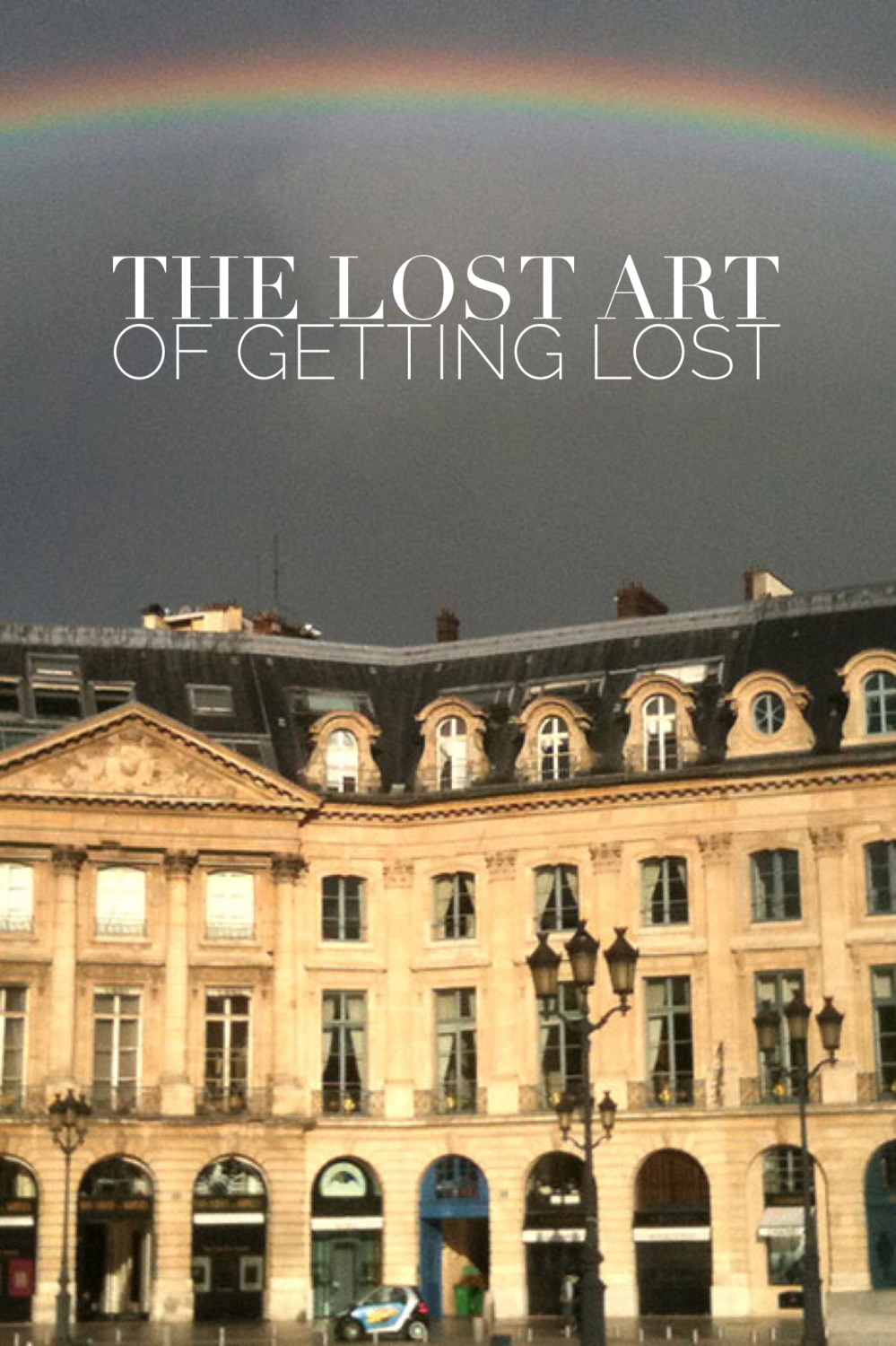

What I remember is two wildly wrong turns, then pulling off to the shoulder to address our tempers, those being lost as well. After finally, finally reaching our hotel near the Arc de Triomphe, I remember wandering Paris by myself for hours in a huff, during which time I took a photo of the coolest rainbow I’ve ever seen, soaring above a magnificent Parisian building.

When I returned to the hotel, we fought some more, but were losing the connotation of our anger. Eventually, we began comparing the solo walks we’d just been on. We had both, it turned out, taken breathtaking photos of that rainbow.

Later that night, a Parisian friend I met up with congratulated me. You haven’t properly done Paris like a local until you’ve been in a screaming match with your loved one on a Paris freeway, she told me. Remember that truism for your next romantic getaway to the City of Lights.

*

Do you remember what it feels like to be lost? I’d forgotten. I’d forgotten the dread of the minutes ticking by, wasted; the lowborn panic of trying to right the ship, as it were; the impatience permeating every new and necessary decision. To be lost against one’s wishes reminds you that you haven’t tamed the world, as you often let yourself believe. Being lost is like trying to learn a new language, only worse because you’re supposed to know how to read a map, you’re an adult.

I’d forgotten about the relief that sometimes comes to the lost person, when she throws a hand to the wind and says fuck it and dips into that café for a beer, and how miraculously, doing so often slows time down enough that when she eventually leaves said café, her bearings have been regained, and how in hindsight that beer becomes the most memorable of the trip.

And now I remember that I was in fact lost once in the time between Paris and Amsterdam, New York. Again, same two people in the car, trying to find the place we’re staying in the countryside of Tuscany before dark. Our cell phones had no bars. We’ve been warned that after dark, we’ll never find it. We take a couple winding turns, hope for the best, then find ourselves in what has to be Tuscany’s smallest village. A woman is walking down the street, and we ask her, via words that might be Italian, if she knows of the place we’re trying to find. We point to it on the map we’ve printed out from the place’s website. She doesn’t speak English, and it appears she doesn’t know the place anyway, but she makes it clear that we should stay put, then fetches her grown son, who does speak English. He works it out with us and we make it to our agriturismo just as the blue of dusk fades to black. I’m amazed that people will take so much time out of their day to help two people who don’t even speak their language. I worry that I wouldn’t be so magnanimous.

*

In that most famous novel of tourism, A Room with a View, the plot requires characters to get lost. Where would Lucy and George have ended up had Lucy, lost in Florence, not wandered into that church for a moment of respite from her pursuit of the path she recognizes? She would never have seen George from a new perspective, in all likelihood. Forster’s wonderful critique of English propriety may have gone nowhere.

Like Lucy Honeychurch, and despite the anecdotes I’ve relayed in this essay, I’ve most often been lost while walking in unfamiliar cities, and it has almost always yielded something interesting. I’ve discovered parks in Paris and ruins in Rome. I’ve happened upon the best little streets in the West Village.

I wonder what might be squandered as we gain the power to always know when to take the next turn. I think we sacrifice getting to know a place on its terms, which if we are to get down to fundamentals, is the only way to truly do it. The experience of a place is little different from any other place if we navigate it only according to how Waze directs us. What’s next? Look at the app. How much farther? Look at the app. If Robert Frost had Google Maps, would he have still chosen the road less traveled?

With navigation in our pocket, we no longer experience a new destination unmediated. We no longer ask directions and then do as the local tells us, keep an eye out for the yellow church before we turn right, try the best pastries in the village because he sent us there. On our own, we no longer suffer the impossible, and impossibly charming, maze that is New York’s West Village. We never stumble into the memorable café to regain our bearings.

It’s been well documented that in the 21st century we no longer spend time bored. The drawbacks of this fact have been discussed widely in the media and elsewhere. Less often documented is that we no longer spend time lost—the result, it would seem, being that we no longer experience the pleasure of finding something.