On our second day on Nias, the Bali-sized island off the western coast of Sumatra, in Indonesia, my boyfriend and I took a long walk down the shore toward the spot where the bay meets the ocean, and then beyond it, just to see what we’d find. We’d chosen Nias for a few days of vacation after some time spent working in Singapore initially because it seemed like a convenient option, geographically speaking. It wasn’t. What might have been an hour-and-a-half flight in a region with better infrastructure took us a full day of travel. First, a flight from Singapore to Medan, on the main island of Sumatra; then another flight to Gunungsitoli on Nias. From there, a three-hour drive brought us finally to the place we’d lay our heads, on Sorake Beach, in Lagundri Bay, down the road from a village called Tulukdalam.

On this beach, in this bay, a traveler will find one of the best surfing waves in the world, potentially the best “right-hander” around. A row of modest guesthouses, known in these parts as losmans, face the wave, and we had booked a cabana in the nicest of them. The losmans are more or less the only places for tourists to stay on the island. The only people who come here either are surfers or, like me, are romantically involved with one.

The owner of our accommodation, a well-weathered Australian surfer named Mark Flint, started coming to Lagundri Bay in the 1980s. He moved here permanently in 1989 and married a Sumatran woman. Today she spends much of the year in Australia while he hangs back in Nias. Flint has the long hair and leathery skin of a guy who has not only lived in surf culture for decades, but hasn’t had to report to an office in just as long. He’s one of perhaps five or six expats in this corner of the world, and he would become a bottomless well of information about the place.

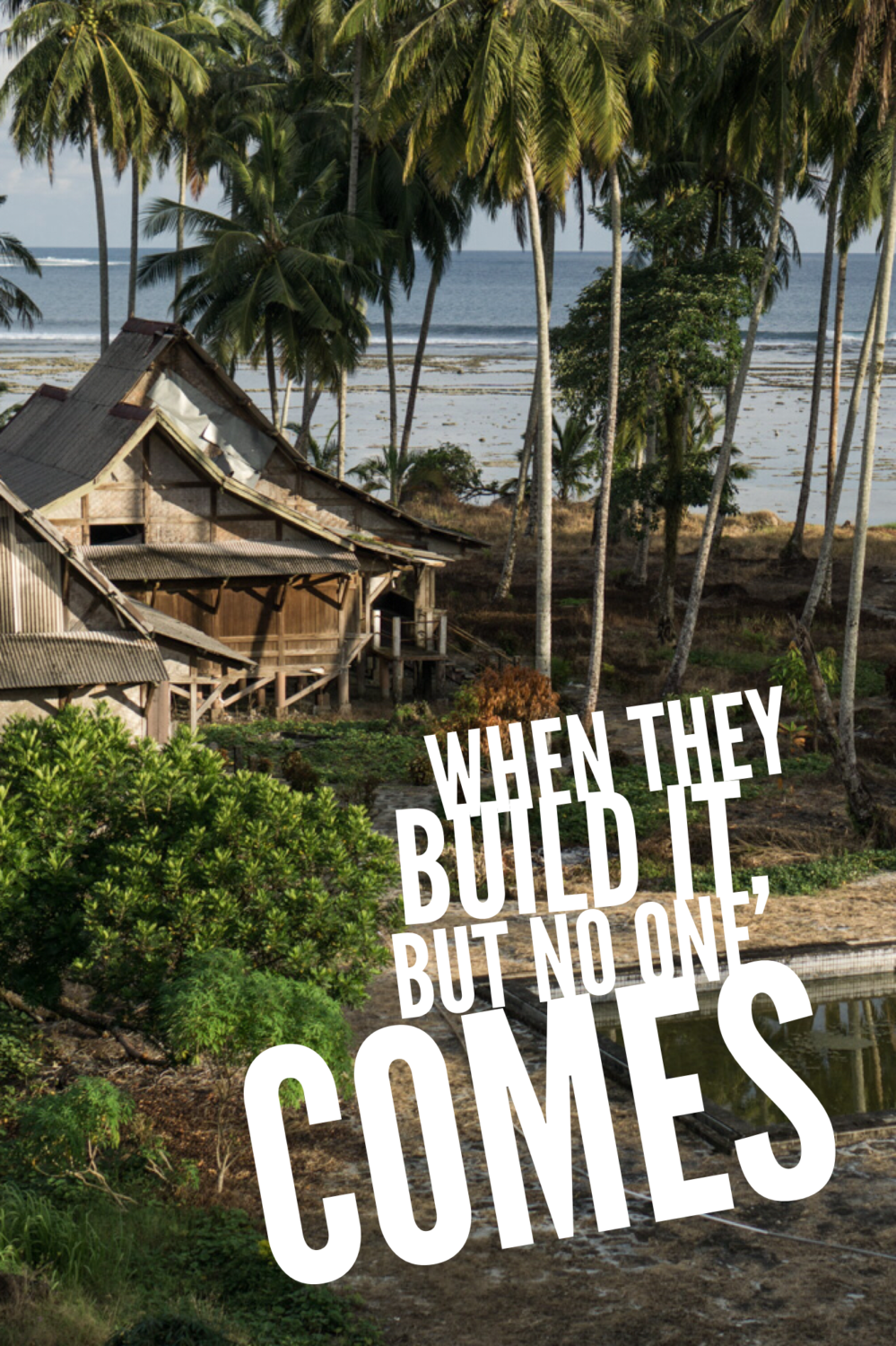

On our second-day walk, we headed past the wave itself, past all the losmans, to where civilization seemed to be thinning out to nothing; there, we came upon some abandoned buildings. Taken together, it quickly became clear, they comprised a former beach resort, the layout of which centered on a pool area. Facing it from the ocean, a building on the left clearly once held the poolside restaurant, with its central enclosed kitchen surrounded by a 360-degree covered terrace, while the relatively enormous main building loomed behind the pool, reminding me every bit of a Dirty Dancing doppelganger in the Upside Down.

Why do I love abandoned places? Their central identity is composed of eeriness, a supposedly negative thing that we always enjoy. There’s no real danger in the eerie, is probably why. But it also has to do with why faded glamour is almost always better than glamour at its peak. Faded glamour has got stories to tell, and so does an abandoned beach resort.

This one in particular seemed full of melodrama, its contrast with the remoteness and poverty on the island all around it giving it an almost paranormal gloss.

We spent an hour wandering the grounds of the shuttered hotel. The Sorake Beach Resort is abandoned, yes, but recently enough so that the smallest use of one’s imagination can conjure a breakfast buffet on the restaurant terrace, a waiter placing a cocktail on the table next to a pool chair, the smell of sunscreen. There’s evidence of the ephemeral nature of everything in a place like this, but also evidence of continuity through time. It’s gone, but it’s still there.

The pool, still filled with water, flashed a glassy green that we estimated would take ten grand to get us into. Between it and the main building, a bush with flaming pink flowers continues to thrive. In the former open-air lobby, it’s easy to see where reception was, where the bar was, where the concierge sat, because their respective counters remain in place. Most surfaces are made of marble and retain a minimalist attractiveness. On one wall, someone had drawn a map of local villages and other points of reference, graffiti-style. It was hard to imagine for whom.

When it opened in 1995, Accor Hotel Group—owner of Sofitel and Fairmont Hotels, among others—ran the place. Mark told me they did so with the understanding that a new airport would soon bring wealthy guests in directly from places like Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Jakarta. Accor ended its management of the resort a few years later, when the speedier travel routes did not materialize.

Behind the reception desk at the Sorake Beach Resort, I got a glimpse through some broken glass windows of a room stacked to the ceiling with mattresses. We peeked into one of the freestanding cabanas, one of 73 total, to see that the furniture remained in place. These bungalows at one time were nicer than almost all of the private homes on Nias. They—whoever they are in this case, long after Accor severed ties with the property—did not repurpose them for the local community. Instead, they locked them up and left them to slowly rot, surely the path of least resistance but also a disconcerting waste in a place of blatant, normalized poverty.

When I talked to Flint about the resort, I also learned that he once worked as its general manager. He showed me some framed photos of the place in its better days–two girls riding bikes around the grounds, mowed grass, open beach umbrellas around the pool. The Sorake Beach Resort closed for the final time in 2010. Flint told me that it survived that long only because of relief funding that came in after the earthquakes and tsunami of 2004 and 2005.

Had it gone a little differently, The Sorake Beach Resort might today come up in the origin story of Nias as a glamorous vacation destination, “the new Bali,” or “the other Bali.” The two Indonesian islands, in almost all ways, are strikingly similar—in size, in climate, in flawless coastlines with world-class waves, in the distinct local cultures that endure on them, in their lush, mountainous inlands.

Fifty years ago, the fortunes of the islands weren’t so different. Both established nascent tourism services in fits and starts in the earlier decades of the 20th century, only to have it all interrupted by World War II. When the seminal Bali Beach Hotel opened in 1963, there were only three hotels on the entire island. Today, there are more than 500. On Nias, on the other hand, you could still count the number of true hotels on one hand.

For reasons of luck and happenstance, mass tourism never descended on Nias, and after that neither did the digital nomads, as they have in Bali. You can’t book a yoga retreat on Nias. You can’t use your hotel rewards points. You mostly can’t even be guaranteed electricity 24 hours a day, not to mention a reliable wifi signal. You can experience a place that is truly interesting, and you can have entire beaches to yourself. It’s a more authentic experience, but I can’t help but also see a population that would have benefited from the economic boost provided by tourist spending.

A walk through the one-time Sorake Beach Resort, then, is an exploration of the what might have been, as much as it is of the what was.