I picked up William Finnegan’s surfing memoir, Barbarian Days, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 2016, not with the intention of reading it front to back, but to consult the passages in which he visits the island of Nias, in Indonesia, a place I’d just come home from 40 years after Finnegan.

My own trip to Nias wasn’t easy, given the relatively short distance I was traveling—two flights from Singapore, then a three hour drive to the only stretch of accommodation on the island. But it was a breeze compared to Finnegan’s:

“We caught a small, spartan, diesel-powered ferry from Padang. It was about 200 miles to Nias, and a storm clobbered us the first night out. We wallowed in total darkness. At times, terrifyingly we seemed to lose steerage. Waves washed across the deck. The only cabin was a small, grimy plywood hut for the helmsmen. Most of the passengers were sick.”

This boat to Nias came partway into a three-year adventure through Polynesia, Southeast Asia, and on to Sri Lanka and South Africa, and it is emblematic of the spirit of this book, its willful abandonment of the limits at which many people would turn back home, or at least toward the nearest Hilton.

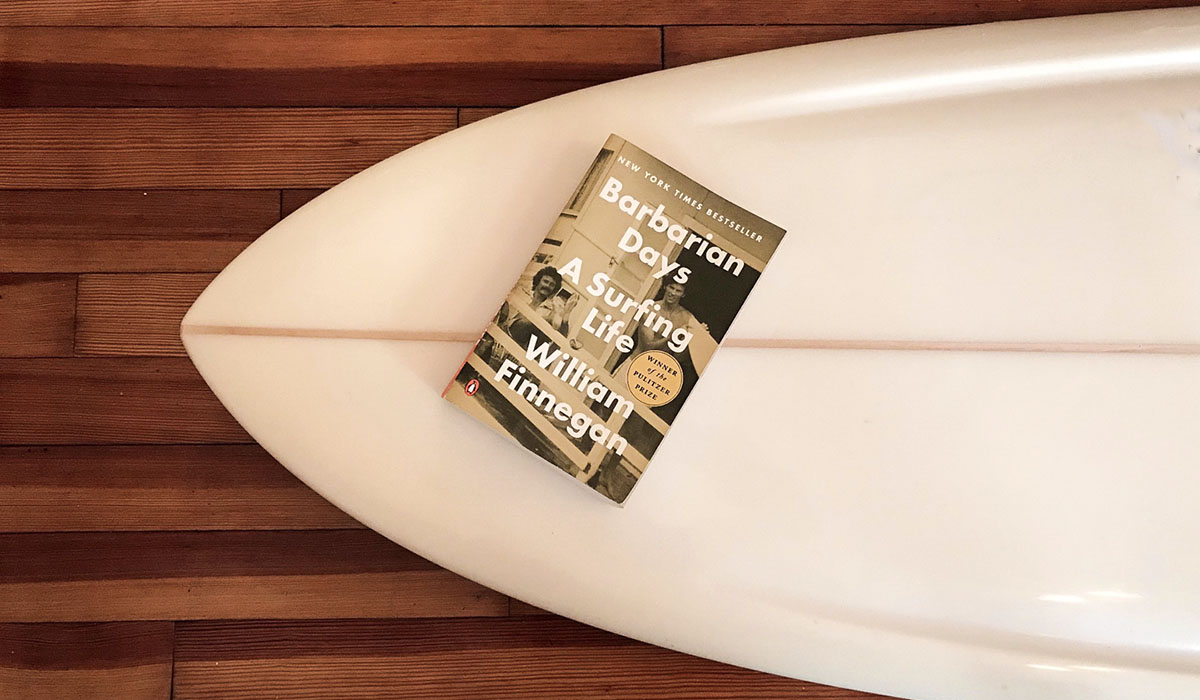

Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life

by William Finnegan

Penguin Book

447 Pages

The “we” in the quoted passage above consisted of Finnegan and his friend Bryan, another surfer from America. Their singular pursuit during these travels was of surfable waves. And in fact Finnegan says he peaked as a surfer on Nias, which has one of the world’s best “right-handers.” He also contracted a malaria that would soon hospitalize him in Bangkok.

Juxtaposing Finnegan’s account with my own was a fun exercise and in the end, it was compelling enough to get me over to page one, then through the entire 447 pages spanning from Finnegan’s childhood surfing in Southern California and Hawaii, through to his later years, now living in New York and chasing waves along the Long Island and New Jersey Coasts.

Today’s self-described daring traveler may find himself humbled, as I was, by Finnegan’s tales from Polynesia and Southeast Asia, where he frequently found himself without access to electricity, or furniture, or protein-based food, or access to medical care, should the need arise. We have lost all concept of what off-the-beaten-path means in this globalized, interconnected world. From Nias, for example, I could still post to Instagram and text with my parents back in the U.S., is what I’m saying.

Of course, Finnegan went to places more remote even than Nias. In Fiji, William and Bryan heard from another surfer about a wave off the island of Tavarua, near Fiji’s main island of Veti Levu. They hired fishermen to take them out, and to return for them after a week. If anything went wrong, they were to light a signal fire when the sun set. The island was rife with poisonous snakes, but otherwise uninhabited. The thing Finnegan missed most after a week or so? The mundane comfort of a chair.

In southeast Java, they paid a local fisherman to supply a ride over to a shoreline of dense jungle in front of which there was a good wave. He also supplied eight jerry cans of freshwater, and a promised but unenforceable ride back a week later. Once he’d dropped them and left, they discovered that six of the jerry cans contained undrinkable water, contaminated as it was with the remnants of fuel. They rationed the remaining two cans, slept on the ruins of a surf camp that had once existed, and listened to the rustling of wild boars below their tree house at night. During their first surf session, Bryan burst an eardrum, and had no choice but to grin and bear it for the rest of the week.

These are the stories that stuck with me. They are the stories of travel pursuits that I would have been too cautious to follow through on. I was also struck by a story that came into the book as a aside: Later in life both Finnegan and his travel buddy Bryan ended up writing for the New Yorker. What are the chances? Far slimmer than surviving a nasty strain of malaria contracted on circa 1979 Nias, I’d say. I would have liked to read more about how that happened.

But this is a surfing memoir. Career and family are generally peripheral. As such, it got a lot of praise for its lengthy descriptions of particular waves. I found most of these descriptions boring, and got wrapped up more in Finnegan’s search for a wave, in the travel itself, and in his relationships, especially with fellow surfers.

Still, the New Yorker informs this book. The tone is that of the 20,000 word feature in that magazine, and in fact long stretches of the book have been adapted from such. It is emphatically even-keeled; Finnegan never loses the disposition of the reporter, even when turning his journalist’s eye onto himself. There’s no melodrama, the detachment in his approach not the kind of cold detachment that can sometimes most effectively communicate the human condition, or at least one human’s condition. There is in his writing, most prominently, earnestness.

Finnegan manages, for example, to get us all the way through five-plus decades of a surfing life without giving us an idea of just how good a surfer he became, or didn’t. He speaks of declining a shot at certain waves that others take on, at the same time a reading between the lines reveals a level of expertise that surely has took him onto some crazy-big waves.

But vagueness of his precise surfing proficiency aside, it’s fun to read about surf culture before it infiltrated popular culture. And it’s fun to read about how travel works when there’s a higher purpose to it. Finnegan didn’t travel for travel’s sake, and that gives his travels a dignity that mere travel often lacks.