There are places on Earth where the past evokes itself so vividly that it seems to exist in the present. Denbighshire County, in northeastern Wales, is one of those places. With borders that stretch southward from the Irish Sea and westward to Snowdonia National Park, its distinct geological profile boasts a sweeping valley (the Vale of Clwyd) and a cluster of hills and mountains (the Clwydian Range; locally referred to as “The Tops”) that reward hikers with astounding views. It is against this backdrop that the past comes alive.

The 1978 discovery of Neanderthal remains, near the city of St. Asaph, established Denbighshire as the longest human-inhabited area in Wales. The county’s many castles and castle ruins are the remnants of Edward I’s brutal 13th Century conquest of North Wales and the (Welsh) last stand in the 17th Century English Civil War. More recently, Beatrix Potter immortalized Denbighshire in her Beatrix Potter the Complete Tales (Peter Rabbit)

Despite all this, Denbighshire today is not a destination familiar to many urbane travelers, though it boasts much that they hold dear: art and culture, farm-to-table cuisine, independent shops, good coffee and local lager. It was a refreshing counterpoint to my home in New York City, with all of that metropolis’ selling points but none of its pretense or chaos. The two towns I got to know during my recent visit to Wales embody contemporary Denbighshire in slightly different ways; each fusing its lush landscape with an endless history and contemporary culture that hits all the right notes.

Here’s a little more about each of them.

Denbigh

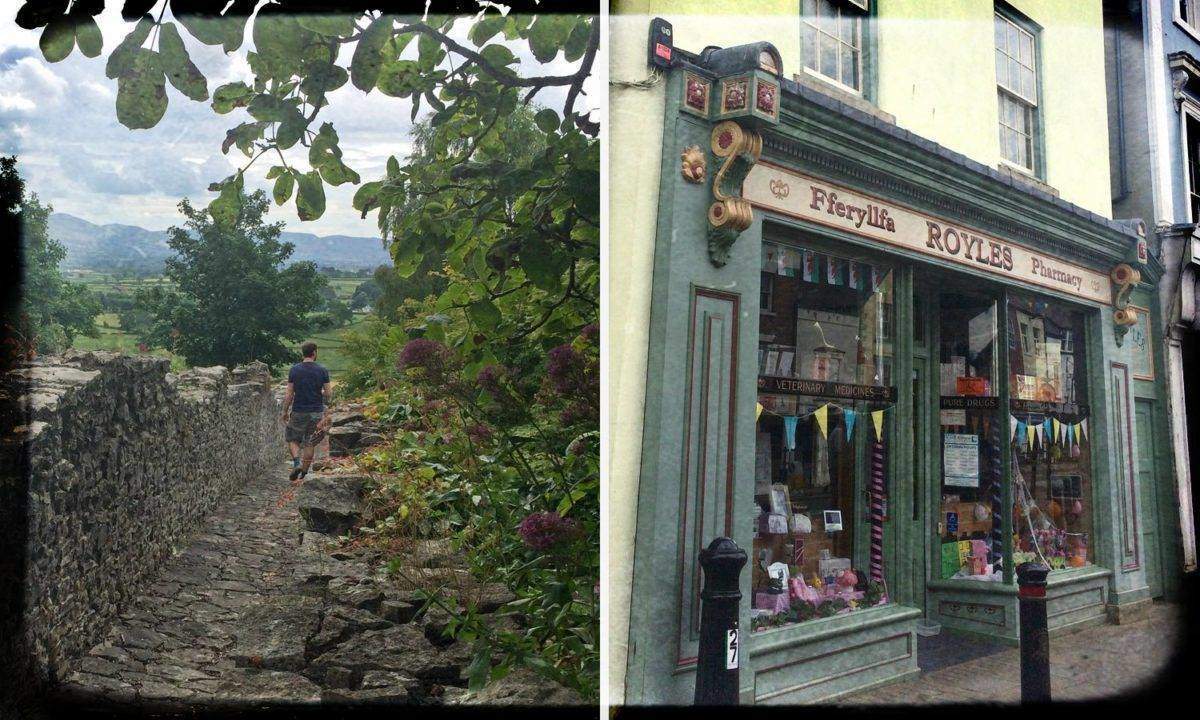

On our first day in Denbigh, we stood on the old city’s town walls gazing at layer after layer after layer of life and its remnants, crumbling ruins of an ambitious Elizabethan folly, centuries-old chimneys stretching still toward the sky, ancient churches dotting the landscape, all surrounded by green mountains and livid sky and dappled with the sweet scent of the sea. In Denbigh, you don’t just walk. You wander. As I did so, I found myself contemplating the footsteps that trod there before mine: those of miners and shepherds, lords and ladies, princes and serfs, soldiers and peacemakers, émigrés and immigrants. These thoughts mingled with those of the returning sons at my side—my husband, who is from here, and our baby boy, whose heritage is.

The Vale of Clwyd’s mythic greenery swaddles Denbigh and its neighboring towns and villages, and added a meditative element to each moment we spent there. We found ourselves on the town walls of this historic market town, along with tourists from England and a handful of game Denbigh natives, as part of an official tour. Led by town councilor Ruth Williams, a native Welsh speaker and local advocate, we traveled through a millennium of local lore in 90 cracking minutes. We wound our way from the town center to toward Denbigh Castle, passing a dizzying array of historically significant sites—Denbigh is home to over 200 buildings on the United Kingdom’s Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, the most in Wales.

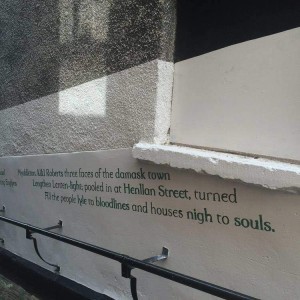

Of these, I was most captivated by the recently revitalized Broomhill Lane. In 2014, a civic initiative transformed Broomhill Lane from a pedestrian afterthought into a public art exhibit ripe with sculpture and poetry: work by Welsh artists overlays walls, windowpanes, lighting fixtures and utility covers, and each piece illuminates an aspect of Denbigh’s history or myth. As a New York resident for the entirety of Michael Bloomberg’s reign, I was enchanted by the Denbighshire government’s choice of contemplative, rather than explicitly commercial, means to draw visitors. Rhys Trimble’s poetry mural and Rebecca Gouldson’s map-inspired utility covers especially stood out.

After pausing at the Burgess Gate, Ruth opened the aforementioned town walls with a key procured from the Library. We walked in the shadow of the vale, awed and silent as we admired opulent private gardens and public parks. The party broke up as we reached the lush borders of Denbigh Castle’s ruins.

Later, I accompanied the tour’s native contingent to The Guildhall Tavern, once the base of the royalist Myddelton family during the British Civil War, now a hotel and restaurant (or “gwesty and bwyty”). As we savored our coffees, the tavern doors burst open and through them flew a procession of local dignitaries in their gilded finery I was soon honored to meet the only man who holds the “key to Denbigh”—revered historian R.M. Owen. He was everything you’d imagine a Welsh man of letters to be: kind, clever and twinkly-eyed. This is fortunate for Denbigh’s residents, as his key affords him permission to enter any home in the town. At any time.

Ruthin

That afternoon, we left Denbigh for an early dinner at the Three Pigeons Inn in nearby Ruthin. As we drove out of the new town and into the vale, I mentally bookmarked the places I planned to return, whether with my guys or with just a book, to nourish my very being.

Ruthin, Denbighshire’s County Town, may not boast as many listed buildings as Denbigh, but its architecture reveals a similarly rich history nonetheless. There we eschewed a traditional tour in favor of a choose-your-own adventure. In Ruthin, as in Denbigh, the local government employs art to highlight its history. We followed the Ruthin Art Walk, guided by some of the 22 hidden figures that rest on rooftops around town. Along the route, street level spy holes revealed diorama-like representations of the heroes and horrors of local legend. Once again, the past was present in Denbighshire. In Ruthin, unlike in Denbigh, the storefronts have a frisson of flash that proved irresistible to us New Yorkers. The options are exceptional, if limited.

In recent years, Ruthin has evolved into a bedroom community for the affluent and upwardly mobile who work just over the English border in Chester and Manchester. Despite its suburban realities, the spirit of Ruthin is as far from Real Housewives territory as can be imagined. The town’s vibe, what I would describe as “pastoral funky,” was beguiling, its residents worldly and eager to share the sights in their side of paradise.

Leonardo’s Delicatessen is what every new Brooklyn market strives too hard to be: unassumingly excellent. Owned by a “master chef” and his wife, Leonardo’s sells a selection of local pantry essentials (Anglesey sea salts), gourmet pies (steak and red wine), contemporary interpretations of traditional pastries (the Ruthin honeybun) and perpetually craved Welsh cheeses.

Although native to Ruthin, the three Choo Choo boutiques in town are stocked with items that wouldn’t be out of place on the streets of Soho or SoHo, with signature home scents that recall country gardens, sumptuous Italian leather accessories crafted in Brit-chic silhouettes, and dresses and skirts with lines that span the spectrum from smart to semi-deconstructed. Apparently, we shopped Ruthin on what was my lucky day: sale racks lined the sidewalks outside of the store.

Next, we ducked into Siop Elfair, the Welsh Craft and Book Shop, drawn in by the Melin Tregwynt textiles featured in the window display: wool blankets and throw pillows in Damien Hirst spot painting-esque prints. There, among the obligatory touristy trinkets, we found a trove of Welsh-made textiles, decorative slate accessories and hand-painted pottery. In other words, we hit the Apartment Therapy motherlode.

That evening, we dined at Myddelton Grill On the Square, a gastropub housed in a Tudor-era building. While our party convened in the front room, I walked my toddler son around the patio, debating the choice of mojito, prosecco or pinot noir. When I made up my mind and we turned back into the building, we were greeted by smiles instead of side-eye. Note to parents with small children: In Denbighshire, babies in restaurants don’t draw the ire they do in the tri-state area.

After a dinner of steak, spoons full of savory shared sides and red wine, the baby’s bedtime beckoned. We left our fellow diners to their revelry in one of the restaurant’s private rooms. As we walked down the lane, the sun still shone brightly despite the late hour, each step away from the restaurant felt like a step away from Denbighshire, and a new melancholy crept onto the aged cobblestones.

Getting There

Denbighshire may be accessed most directly via England’s Manchester Airport. Travelers interested in a scenic route (and a broader Celtic experience) can take a ferry from Dublin to Holyhead, on the Welsh Isle of Anglesey, then a train to either Rhyl or Prestatyn.

-by Sacha Phillip Wynne. Except where noted, photos by Sacha Phillip Wynne.

Note: The author’s sister-in-law was once employed by the Denbigh Town Council, and played a role in the Broomhill Lane restoration. The author’s nephew is currently employed by Myddleton Grill On the Square as a barman.