Perhaps no other American author has had his writing style more widely examined, more often imitated, and more intensively deconstructed than Ernest Hemingway. No one seems able to get their head around the intricacy he brings about via such simplicity. Hemingway used only the most necessary words, then pared them down even further. He employed understatement to suggest depths of drama and emotion. He left the most important things out and made them all the more compelling for it.

Swaths of writers who came after him, from Jack Kerouac to Raymond Carver to Joan Didion, developed their own writing identity only after copying his. We, like them, wonder where did he learn it, and from whom. But Hemingway didn’t aspire to write like any other writer. Instead, he wanted to write the way Cézanne painted. In service of understanding this influence more viscerally, I ended up at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art one sunny afternoon this spring.

I was, incidentally, following in Hemingway’s very own footsteps. He came to this museum in 1950 with his son Patrick, his wife Mary, and the New Yorker writer Lillian Ross, who wrote about the outing for the magazine. He did not much care for New York City—“This ain’t my town,” he said—and took pride in never having lived here. He stayed at the Sherry-Netherland, caught up on some shopping needs, and like any schmuck, made a date to see an old friend while he was passing through. That the date was for champagne and caviar with Marlene Dietrich did not change the fact that Hemingway was a tourist in this town.

And as a tourist, he wanted to see the Cézannes at the Met. Doing so would remind him, perhaps, of when he first discovered the painter’s work decades earlier in Paris. “I learned to write by looking at paintings in the Luxembourg Museum in Paris,” he told Ross. In the 1920s, the Luxembourg still held the great Impressionist works that have since dispersed to the Musee d’Orsay and France’s National Museum of Modern Art. The timing for the painter to impact the writer was right: Cézanne left this world seven years after Hemingway came into it, an ocean away.

In New York in 1950, Hemingway and his entourage spent two hours wandering the galleries at the Met, with Hemingway growing most excited by the Impressionists. He homed in on Cézanne. He called him a “wonder painter.” He stood for a long time in front of Rocks in the Forest (formerly known as Rocks—Forest of Fontainebleau), in particular, appreciating the human struggle suggested by the rocks themselves.

I wasn’t sure how much Cézanne I’d find at the Met, but when I got there I discovered a whole room of it, and then some. I sat on one of two benches in the middle of that room and took the 16 paintings in, passively at first, like the person tired from walking that I was just then. I was soon joined on the benches by a group of teenaged girls who might have been loud but weren’t. In the doorway, a guard stood, younger than most museums guards but no less bored.

From my vantage, the paintings assembled themselves into a collective whole, with observable common traits. The most profound of these, from a distance, was the colors. The reds and the greens and the purples were somber versions of themselves; masculine versions of themselves. Idris Elba would wear these colors. They were shades of colors that aren’t afraid to get dirty, or that evolved with getting dirty in mind. These were sturdy colors, no-nonsense colors, colors pared down and then pared down even further.

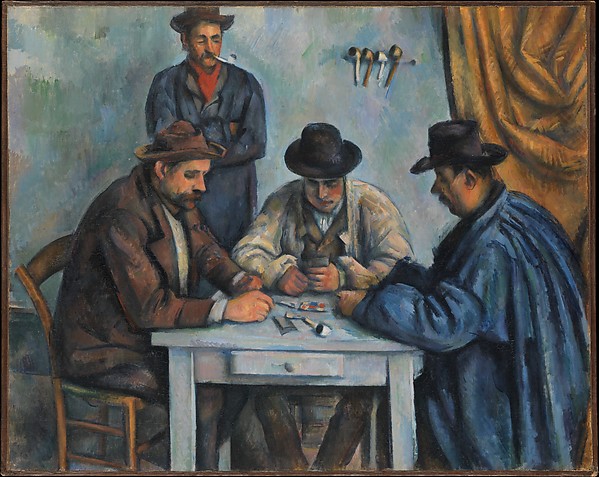

I was facing the painting in the center of one wall straight on: The Card Players. It’s one in a series of five paintings with the same subject. Three men sit at a blue table considering their hands, while a fourth man stands and looks on. I moved closer and discovered my favorite part of the painting—a row of smoking pipes hanging behind the men on the wall. It’s a detail Hemingway would have to love, because it tells you more about the story of the scene than any of the action or any of the men’s intensity.

To my left, a row of still lives lined the wall. In these, the fruits exude a sense of permanence that no fruit deserves. They are beautiful, but also stern. They seem meant not to stir emotions but to control them. Cézanne is reducing the fruits to their elemental shapes, and you can see them bursting out of the Impressionist tradition and rolling headlong into Cubism. Cézanne is quoted as saying that he wished “to make of Impressionism something solid and durable,” and that’s easy to see.

Aesthetically speaking, Cézanne is not generally kind to women, which would have suited Hemingway well. Cézanne’s hand thrives with the concept of masculinity, and even the women he depicts don’t escape its grasp, as evidenced by Madame Cézanne, a portrait of the painter’s wife in which he makes her severest features even more so. Her hair is pulled back rigidly, her expression is pursed, and her shoulders are those of a linebacker. It is not a beautiful painting. In fact it seems intentionally to be the opposite.

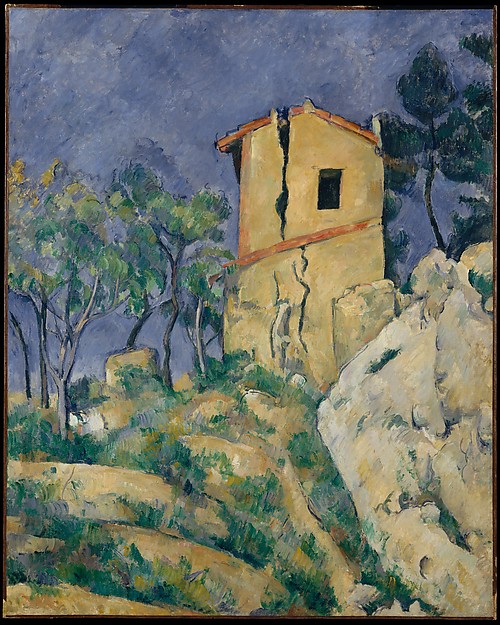

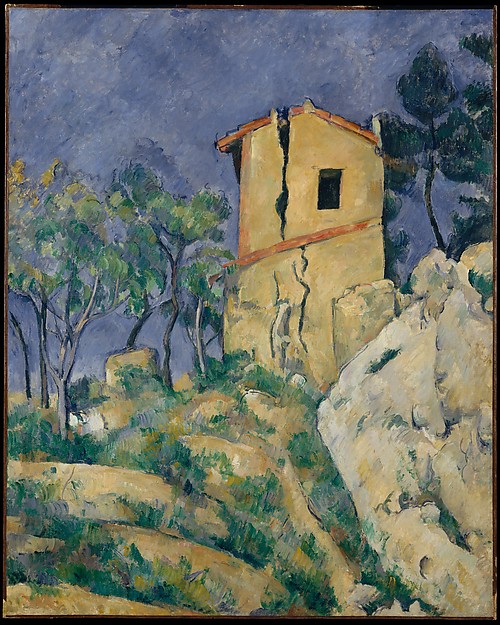

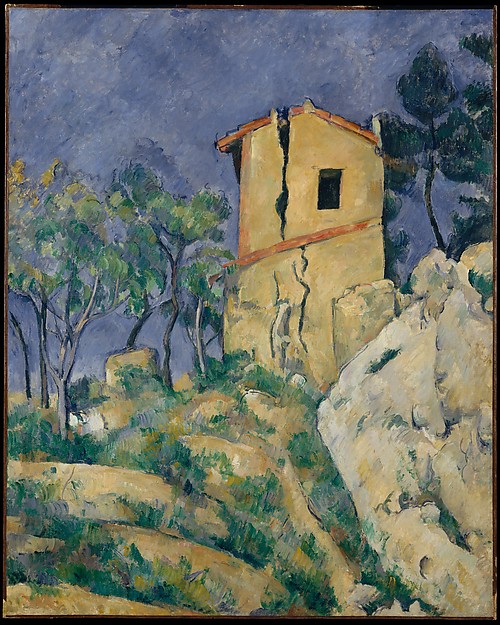

Eventually I headed to the next room over, where five more Cézannes mingled with some Picassos and such. One of these five was The House with the Cracked Walls. The “sinister crack”—as described by the museum on the label next to it—in the building is one of those seemingly simple details that implies infinite backstory. It’s just the kind of detail that Hemingway would have used in a story to get at the history of a place or the layers of human drama that unfolded there.

I think about that crack and I think about Hemingway’s prose, how in the opening paragraph of A Farewell To Arms, “[t]roops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees,” and how you know so much after reading it, and how Hemingway makes such a fabulous lens through which to view the 21 Cézannes on display at the Met. The Met, for all of its overwhelming comprehensiveness, can tell stories through the details held within it, too.