“My journey seemed perfect, well, at least one part of it—a dolphin swimming in a kitchen sink.” I wrote these words in a diary on January 3rd, 2003. I have no idea why. They may not even be my words. I would not write them now, reality television having abducted the concept of “journey” for its weight-loss and amateur talent shows, where we hear it spoken before the onset of maudlin piano or swelling strings. On January 6th, I find this: “Ask ‘A’ about her form of epilepsy, see if it ties in with time elision or time subduction—a mild form of narcolepsy?” For the next seven days, I visit Brussels and Amsterdam. I write things like, “Artaud, Peter Sellers, Tate Modern,” and, “Horses drinking out of an old enamel bath, a dovecot, mole hills, a Jewish cemetery, permission to enter the tunnel.” Again, I have no clue why I wrote those words. In Brussels, I note that René Magritte and Paul Delvaux drank in La Fleur en Papier Doré and that a pregnant tabby cat rubbed herself on the brass fittings there. And, in Amsterdam, the prostitutes near the Oude Kirk looked like statues of saints in curving church arcades. The entries stop abruptly on January 19th. “You go away for a long time and return a different person—you never come all the way back” —Paul Theroux, Dark Star Safari.

On the 20th of January, an ambulance took me to University College Hospital, London, and then on to the Middlesex Hospital because of acute pancreatitis and resultant complications. “It brings the unknown. A journey awakens all our old fears of danger and risk. Your life is on the line. You are living by your own resources, you have to find your own way, and solve every problem on the road. What to eat, where to sleep, what to do if you get sick.” —Theroux, interview, Salon 2012.

Once I had regained consciousness and when I had the energy, I read novels, mostly light stuff, Jonathan Coe, Roddy Doyle, Nick Hornby, some crime fiction, nothing taxing, no Henry James, no William T. Vollmann. My diary tells me that I soon became bored with this light fare and moved on to nonfiction. I had read Paul Theroux’s The Mosquito Coast and Saint Jack but had never read his travel writing. I needed to escape the drab ward, the gastrointestinal miasma, the institutional racism and bureaucratic humorlessness. “Whatever else travel is, it is also an occasion to dream and remember. You sit in an alien landscape and you are visited by all the people who have been awful to you. You have nightmares in strange beds. You recall episodes that you have not thought of for years, and but for that noise from the street or that powerful odor of jasmine you might have forgotten.” —Fresh Air Fiend.

What happened next drove me elsewhere. First published in 1794, A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre, in which de Maistre locks himself in his room and explores its walls and furniture, uses memory and digression to travel outward while journeying inward, the enclosed environment becomes the world, all worlds. De Maistre is the Magellan of the microcosm, the Drake of the domestic, the Cook of the claustrophobic. Although the ward I was in had beds for 20 patients, these people were seriously ill. We rarely spoke to each other, retreated into sleep or drugged unconsciousness, and we hid behind newspapers and books. The ward was sectioned off into groups of four beds, two beds facing another two. My bed was by the window, and I kept the curtains surrounding it closed whenever I could. This was my world, this bed, this pink-curtained enclosure. I was not well enough to even visit the toilet, I had a catheter and used a bedpan, not that I needed them that often, I was not allowed to eat or drink, merely wet my gums and tongue with a small sponge. I sometimes managed to shuffle and drop into the chair beside my bed. “Travel, its very motion, ought to suggest hope. Despair is the armchair; it is indifference and glazed, incurious eyes. I think travelers are essentially optimists, or else they would never go anywhere.” —Fresh Air Fiend.

If we take de Maistre’s A Journey Around My Room as one point of our travel compass then the antipodal volume must be Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. Published in 1922, the memoir recounts Robert Falcon Scott and his team’s harrowing and tragic expedition to the Antarctic between 1910 and 1913. He writes, “We had been out for four weeks under conditions in which no man had existed previously for more than a few days, if that. During this time we had seldom slept except from sheer physical exhaustion, as men sleep on the rack; and every minute of it we had been fighting for the bed-rock necessaries of bare existence, and always in the dark.” And this is what it felt like for me to move from my bed to the armchair—a fusion of de Maitre’s miniature journey and Cherry-Garrard’s epic one. Somewhere between these classics of travel literature, between imagination and fact, are Bruce Chatwin, Jan Morris, W.G. Sebald and Paul Theroux. And, at that point in my life, Theroux became my Virgil, my Beatrice. “The difference between travel writing and fiction is the difference between recording what the eye sees and discovering what the imagination knows.” —The Great Railway Bazaar.

Reading the diary again, I realize that some of it was written in retrospect. For the first month, I was incapable of writing. Then, on February 24th, I wrote, “This is will power. I cannot swallow.” On March the 10th, a day after having my gallbladder had been removed, I was sweating profusely, had abdominal pains and was suffering from exhaustion. I could just about make it to the chair but could not concentrate enough to read. I barely mustered enough energy to listen to the radio, to write down notes that are now unfathomable scribbles. My teeth felt inches apart, my nose like that of an anteater, my ears pendulous and scaly. I sat in the chair and noticed how my arms were welted from needles and cannulas and that, “the rectangular remains of plasters and dressing gauze made my body look like an old leather suitcase from which the destination stickers had been removed.” Maybe I was seeking answers and not happiness or just searching for the truth knowing it wasn’t there. “Travel is at its most rewarding when it ceases to be about your reaching a destination and becomes indistinguishable from living your life.” —Ghost Train to the Eastern Star.

On March 13th, the doctors said I could drink and eat. Because of drastic weight loss, they gave me a high-energy lemon-flavored drink. I noted that it was the second-best drink I had ever had, the best being an ice-cold bottle of Becks I had swallowed in two gulps at the Palais Jamais in Fes, Morocco, after an eight-hour taxi journey through mountains and across desert scrub from Marrakesh. I ate some kind of soup but I didn’t know what. I guessed at asparagus, as it was bland and greenish. There was a large red lump on my right arm where they had inserted and recently removed the total parenteral nutrition line. The next day, doctors, nurses and anaesthetists attempted to cannulise me for further procedures but my veins were shot, disappeared, knotted. After two hours and numerous proddings, they managed to get a trocar needle into my right hand. An hour later, the doctor told me it was in the wrong hand and had to come out. The red lump was burning, growing. They had to re-cannulate. I had septicaemia. At the bottom of that day’s diary page I had written, “Re-reading—Paul Theroux—Mosquito Coast.” “It is hard to see clearly or to think straight in the company of other people. What is required is the lucidity of loneliness to capture that vision which, however banal, seems in your private mood to be special and worthy of interest.” —The Old Patagonian Express.

A Sunday, three days later, after a course of intravenous antibiotics, I was feeling slightly better and wrote that “The Mosquito Coast is better than I remember it,” that I hoped to go for a walk but that “I am shaky from the insulin ingestion.” Probably inspired by the Theroux, I tried to remember the novel set in Mexico I was planning to write, “The Spear and the Cross? Or some bollocks like that.” And I had noticed that the “patients trail their drip stands behind them looking like spectral fairground workers back-riding invisible bumper cars.” Did they? Theroux took me to other places, away from the medicinal/corporeal smells of the hospital and gave me the odor of jasmines, the taste of exotic fruits, the meeting of strangers, the naivety and egotism of the traveler. Like travel, here in hospital meant “living among strangers, their characteristic stinks and sour perfumes, eating their food, listening to their dramas, enduring their opinions, often with no language in common, being always on the move toward an uncertain destination, creating an itinerary that is continually shifting, sleeping alone, improvising the trip.” —Ghost Train to the Eastern Star.

On Monday, March 17th, I had high ketones readings in my urine, hyperglycaemia and the scar across my umbilicus, through which the surgeons had removed my gallbladder, felt tight and itchy. My body had become the most visited region on earth, no fold or valley left un-prodded, no arterial system un-navigated, no organ unexplored. Probes had visited my Ultima Thule, multiple hands had palpated my Hyperborea, multiform bacteria had invaded my Agartha—my very core. Charted, written about, discussed, photographed, X-rayed, CAT-scanned, my body would never be the same. If it were a geographical place, there would be maps, guides, gazetteers, GPS coordinates, topographic and bathymetric charts. Our body remains mostly exotic to us; we rarely gaze into its depths. “A true journey is much more than a vivid or vacant interval of being away. The best travel was not a simple train trip or even a whole collection of them, but something lengthier and more complex: an experience of the fourth dimension, with stops and starts and longueurs, spells of illness and recovery, hurrying then having to wait, with the sudden phenomenon of happiness as an episodic reward.” —Ghost Train to the Eastern Star.

The entry for the next day, Tuesday, March the 18th reads, “Out.” There are no further entries until 30th March and these words, “Reading Sunrise With Seamonsters. Another attack of pancreatitis.” Theroux had taken the title of this book from an unfinished painting by J.M.W Turner. Critics argue whether or not the painting shows sea monsters, the pinkish things in a dawn landscape could just be fish in a net. If I stare at the painting, I see my pale skin, the reddish incisions, the stitches in and across my umbilicus; these are the clouds, the monsters, the nets. “Travel, which is nearly always seen as an attempt to escape from the ego, is in my opinion the opposite. Nothing induces concentration or inspires memory like an alien landscape or a foreign culture. It is simply not possible (as romantics think) to lose yourself in an exotic place. Much more likely is an experience of intense nostalgia, a harking back to an earlier stage of your life, or seeing clearly a serious mistake. But this does not happen to the exclusion of the exotic present. What makes the whole experience vivid and sometimes thrilling is the juxtaposition of the present and the past.” —The Happy Isles of Oceania.

On March 31st, the handwriting is ragged, shaky and I can barely make out the words—anaemic, shock, crash. On April 2nd, the entry reads, “right gastroepiploic artery embolized” and then “20 minutes to live.” Two days later, I wrote, “splenetic artery embolized,” followed by “24 hours to live. Seriously ill.” I’d watched them burn a route through my abdominal arterial system to create blood-flow bypasses. My girlfriend had been called in three times because I “was not going to last the night.” I did, obviously. Joan Didion, wrote, “Certain places seem to exist mainly because someone has written about them.” And that’s how I felt, that my body existed only because of the symptoms, only because my doctors were reading me, writing my future in their notes and prescriptions, and there was “a sudden blurring, a slippage, a certain vertiginous occlusion of the imagined and the real”—Didion again. Why had I also written during these days, “Kurdish refugee. Gold bag. Cancer of the tongue”? Did I feel stateless? A refugee from my own body? Perhaps. Maybe my body was the gold bag, precious and yet empty. I certainly did not have cancer of the tongue. Or did I imagine another organ rotting away, full of poison, the words dead, the sentences still born? “Travel is a state of mind. It has nothing to do with existence. It is almost entirely an inner experience” —Fresh Air Fiend.

Thirteen years later, Chitose, Hokkaido. I had moved to Japan in July 2006. “Most travel, and certainly the rewarding kind, involves depending on the kindness of strangers, putting yourself into the hands of people you don’t know and trusting them with your life.” —Ghost Train to the Eastern Star.

I will allow Drs. Atsushi Hasegawa and Atsuhi Nobuoka of the Department of Gastroenterology, Chitose City Hospital, to explain what happened. “He has felt nauseous and thrown up since December 16th, 2006. At about 22:30, December 18th, he suddenly fainted in his room and was rushed to the emergency care unit of this hospital by ambulance. He became hospitalized with coma by diabetic ketoacidosis. He was in a coma and in a state of shock (his blood pressure 60/20), accompanied by acute renal failure by dehydration, pancreatitis and bacterial gastroenteritis. We diagnosed his illness as diabetic ketosis, coma, hypovolemic shock, acute pancreatitis, and paralytic ileus. He went into the intensive care unit. On December 24th, he recovered consciousness. His blood-sugar level was under control by insulin injection. Acute pancreatitis and ileus was also cured. He started eating food on December 25th.” Once I had regained consciousness, one of the first things I asked for was a book, a collection of travel writing—Paul Theroux’s To The Ends of the Earth. “Whatever else travel writing is, it is certainly different from writing a novel: fiction requires close concentration and intense imagining, a leap of faith, magic almost. But a travel book, I discovered, was more the work of my left hand, and it was a deliberate act—like the act of travel itself. It took health and strength and confidence.” —To The Ends of the Earth.

-by Steve Finbow

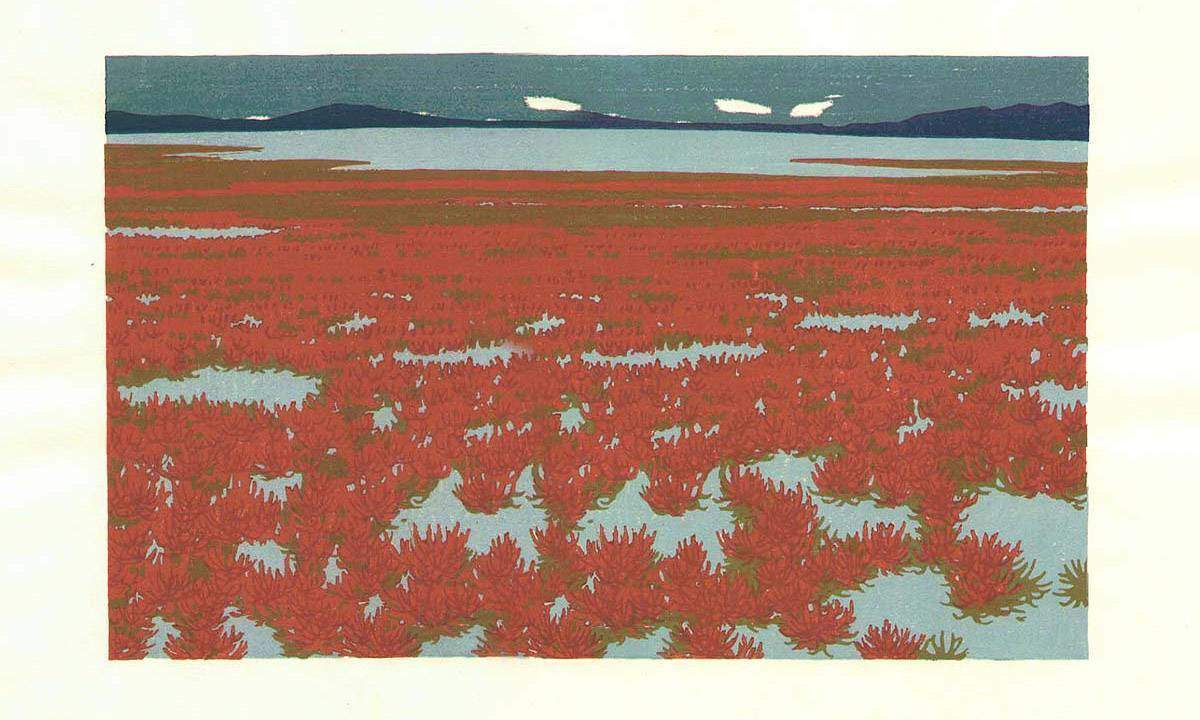

Feature Image: “Twenty-one Views of Ezo – Coral Plant at Notoro Lake,” by Omoto Yasushi