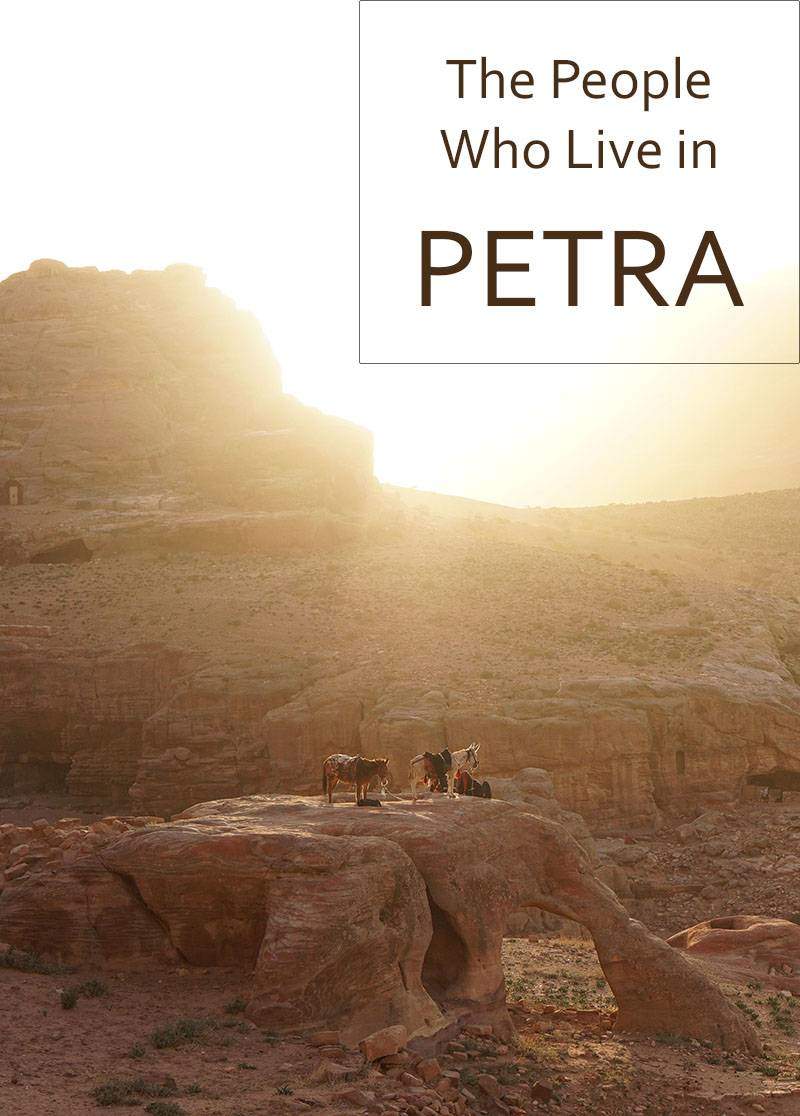

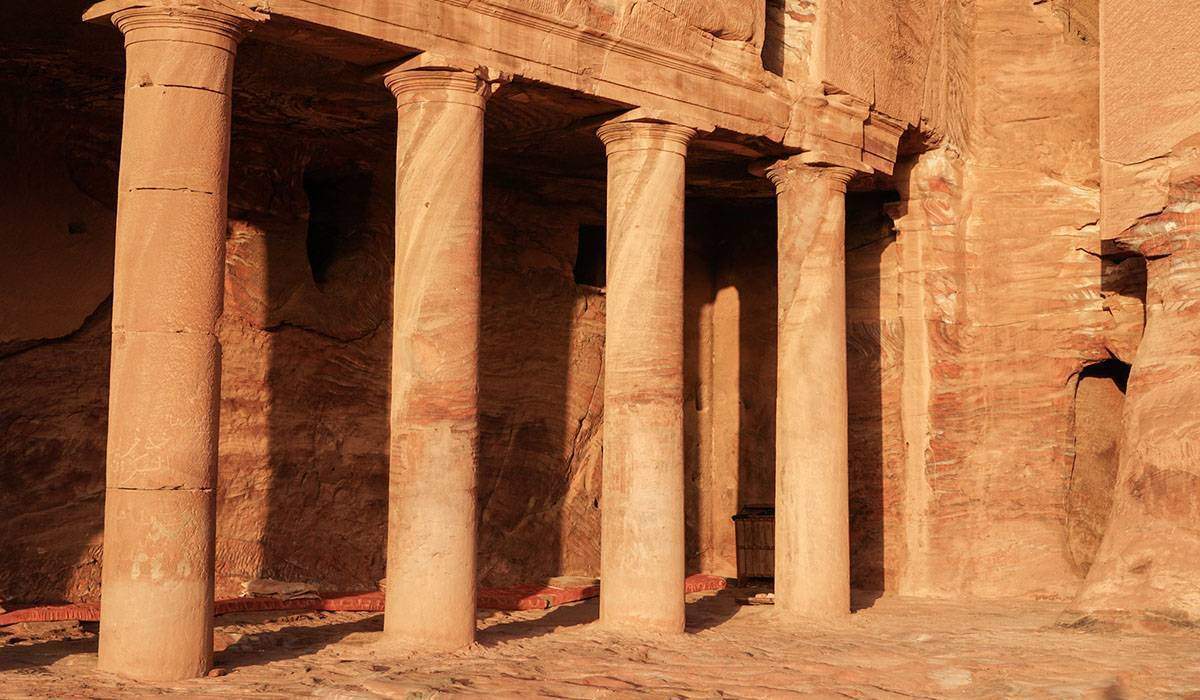

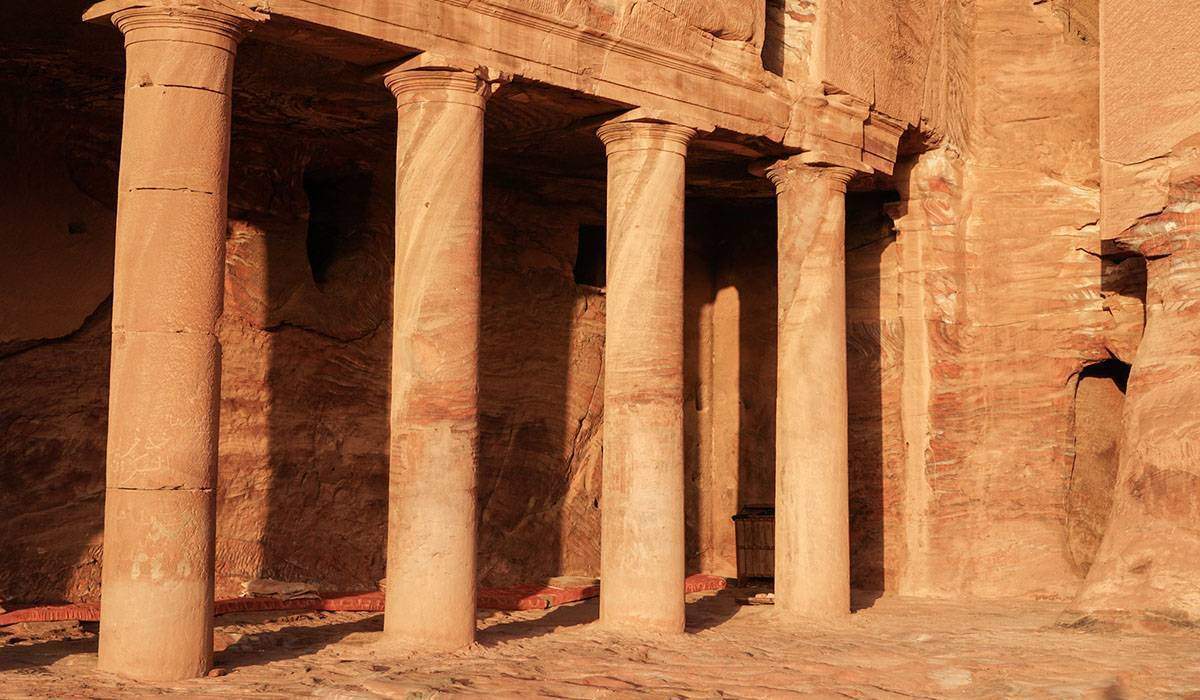

Not long after arriving to Petra, the ancient city in southern Jordan known alternately and aptly as the Lost City and the Rose City, my two companions and I climbed a series of staircases carved into cliffs, which deposited us finally onto a large terrace. At the far end of it, a large room had also been carved into the cliffs, along with an impressive façade of columns and windows. The room, like all the others here, was built to be a royal tomb of the Nabataeans, the people who once dominated the region and who built Petra. We explored it and then returned to the terrace; the sun was beginning to set and this seemed an ideal place from which to appreciate it.

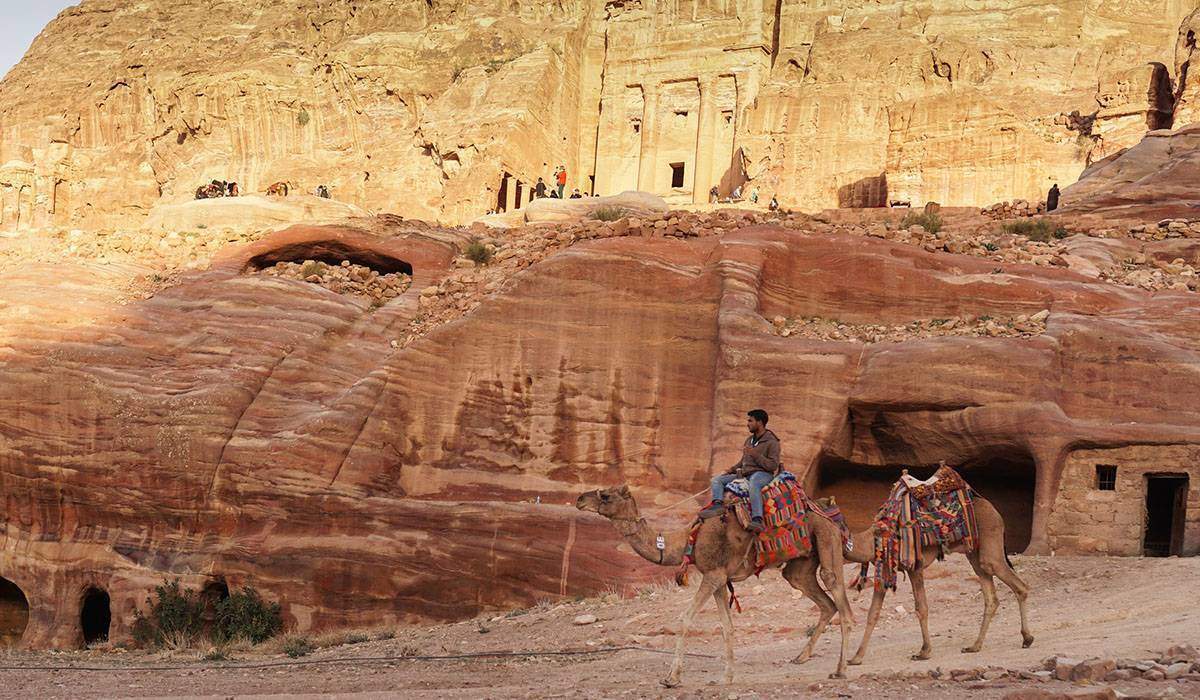

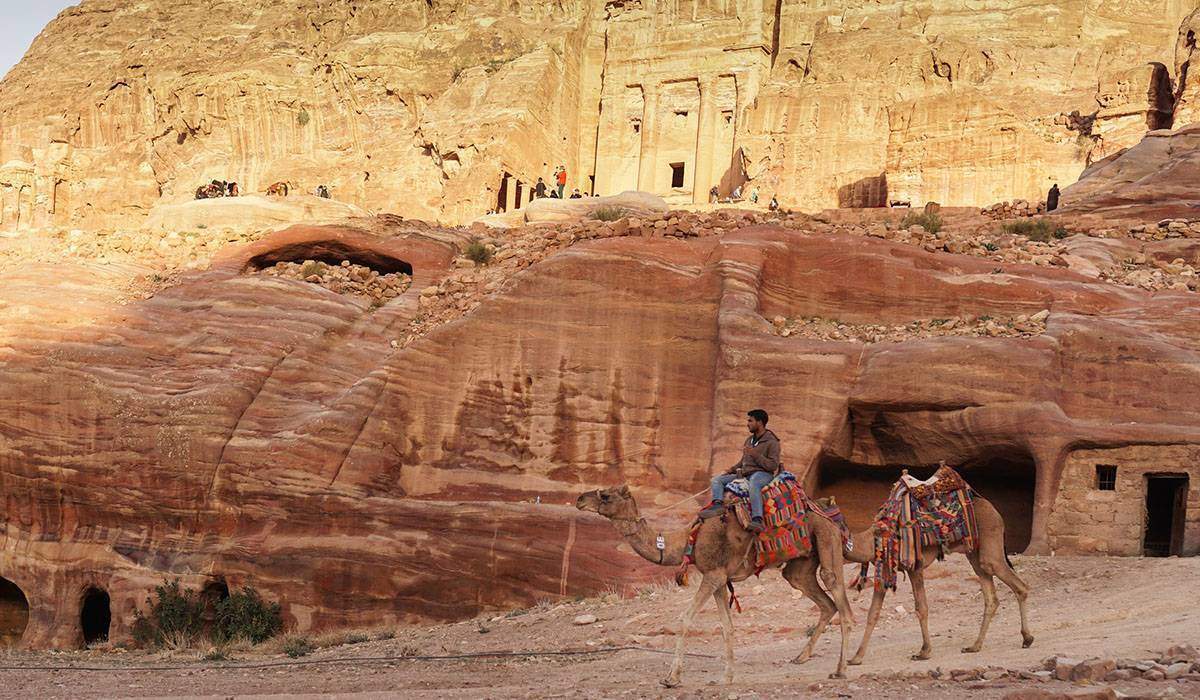

Earlier, we’d walked through what is known as the Siq, an impossibly narrow gorge that lets visitors out onto the famous Treasury building. Most written coverage of Petra gets stuck here, but in fact that building—not a Treasury at all, but one of the grander tombs—is just the beginning of a sprawling old city that remains remarkably intact. After taking in the cacophony of camels and donkeys and hawkers at the Treasury, we’d walked on, down another gorge that soon opened up into a desert punctuated by dusty pink cliffs. On the left, an amphitheater was carved out of one of them. It once seated as many as 8,500. On the right, we found the staircases to more tombs.

And they showed no apparent economic interest in us. The talkative one told us we’d picked the best spot in Petra for sunset. I noticed they were handsome, with their charcoal eye makeup and checkered keffiyehs (cloth headdresses). The same one pointed across the valley to some caves and told us he lived in one of them. My biggest regret, the minute I think of that trip last December, is that I didn’t ask him to elaborate.

A better journalist, or at least a more instinctive one, would have asked the right follow-up question immediately. Can I see it. Or at least, What’s that like. Instead, I asked, Which one? And he pointed to the one with a red door way across the valley, which proved nothing. And then the conversation dropped.

My Lonely Planet guidebook (which served me well) recommends a visit to the home of one Bdoul Mofleh, who lives in one of Petra’s caves and keeps a beautiful garden just outside its door. I Google him. Enough travelers have visited him that I am able to see photos of the inside of his home, of his garden, and of the man himself. The kinds of sites that might check facts describe him as one of the last remaining residents of Petra. A lot of random blogs call him the very last one. His shoes seem permanently dusty and he seems to have a perpetual weathered smile to offer.

Could one live in Petra, and would one want to? Questions spew forth now, in hindsight, from my apartment in Brooklyn. Where do you shower? How do you stay warm in winter? Is there electricity? Do you go to the grocery store? Do you ever bring girls home?

And finally, Do you really live in Petra? More likely, I think, he lives in his parents’ house in Umm Sayhoun and crashes in his cave when he needs to get away, or to reclaim his sense of independence. I’d have done exactly the same, at a certain age, if I’d had access to a cave home. More likely still, he was just telling a tourist what she wanted to hear.

But if I were him, I’d want my own space in Petra, too. Ever since I saw it for myself, I’ve been saying that Petra is one of the rare places on earth that lives up to the expectations set by guidebooks, and by wonders of the world lists, and by Instagram. Even though you know it’s coming, as you approach the Treasury via that narrow gorge, then catch the first sliver of the building up ahead, then a minute later emerge into the room-like expanse that the Treasury overlooks, you can’t help being struck dumb. I feel lucky that I got to see Petra with my own eyes, and at this jaded date there aren’t many things about which I can say that. I am awash with gratitude; it’s so unlike me.

On our second day at Petra, we took a cab to the little known back entrance and hiked to the Monastery from there. This involved first a long descent on a dirt road into the part of the desert that holds the ruins of the old city. We were joined for a few minutes by a group of local kids who’d just been let out of school for the day. They expressed in their perfect English that they wanted very much to take photos with us. (I won’t be posting those here, because they are obnoxious.) They gave us directions to the Monastery. These kids lived in Umm Sayhoun, but their parents worked in Petra and they were headed to find them. It doesn’t feel like a stretch to think of one of them laying claim to his own cave before the decade is out.

Related: 10 Ways To Get the Most Out of Your Trip to Petra

-Words and photos by Sarah Stodola