Fifteen miles west of San Sebastian along the coast of northern Spain’s Basque region sits a small fishing village called Getaria. When it is known, it’s for a couple of things: its Txakoli, a lightly sparkling white wine unique to the region and served in the charming seafood restaurants to be found in the old town; and as the birthplace of the fashion designer Cristóbal Balenciaga.

Born in 1895, Balenciaga grew up learning how to craft a garment, partly from his seamstress mother, and partly thanks to a wealthy patron who helped fund his sartorial education. He soon made his way to San Sebastian, where he opened his first boutique in 1919, and eventually to Paris, where he joined the ranks of Chanel and Dior—haute gods. But it’s Getaria where he is buried, and the town claimed him as its own when it opened a museum dedicated to his work in 2011.

During a visit to San Sebastian, I spent a blustery day exploring the Balenciaga collection and town. The very contemporary museum building looms above the old town, which in turn hugs the water. It’s a pleasant place to spend a day away from the inevitable crowds and commercialism of fabulous San Sebastian. I got off the bus, got my bearings, climbed the hill from the main road and entered the museum, with its soaring serious spaces and echo-y quiet.

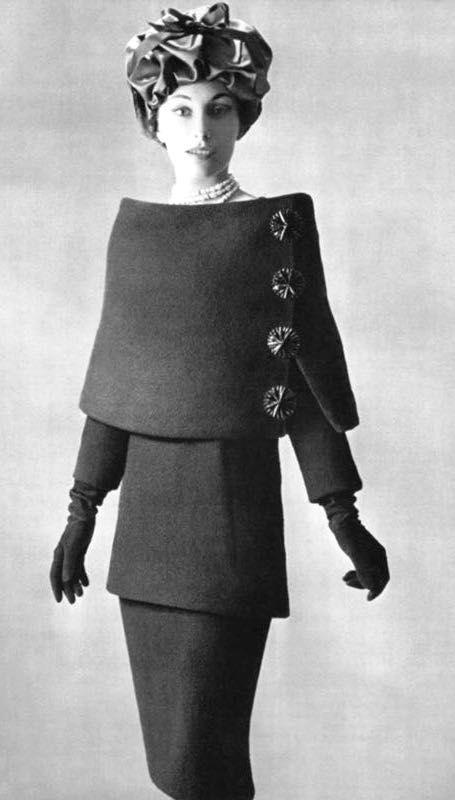

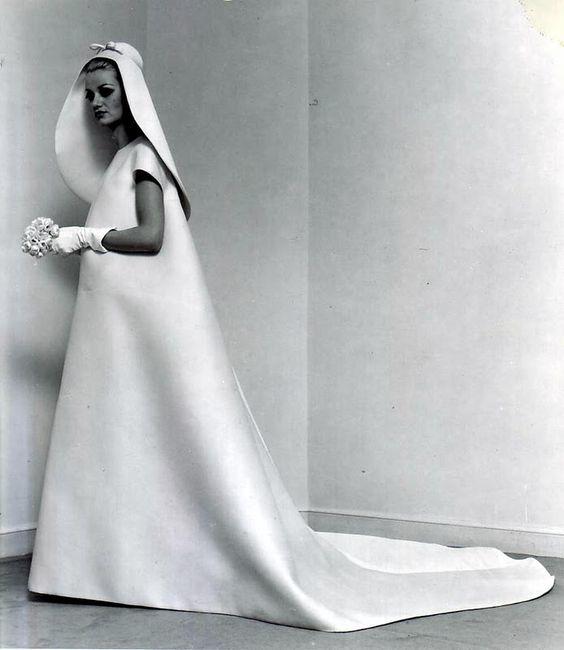

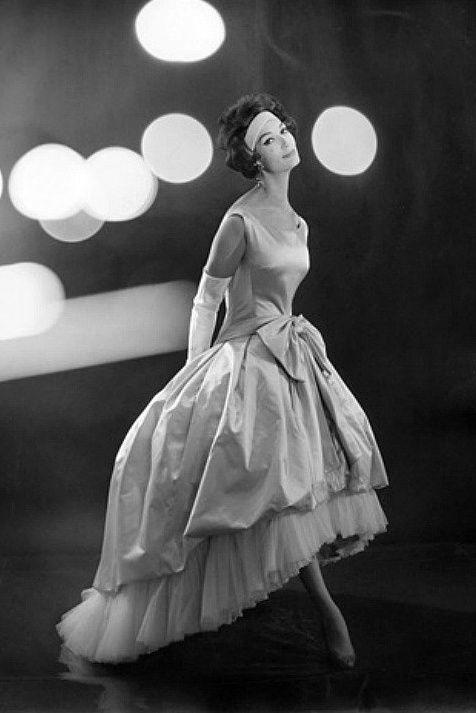

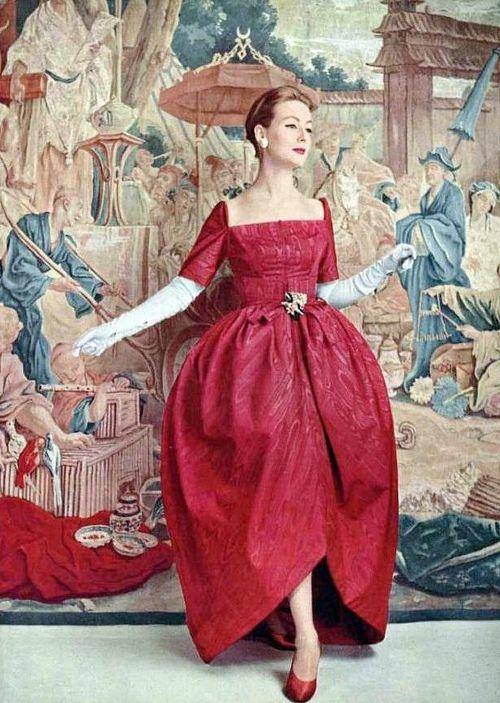

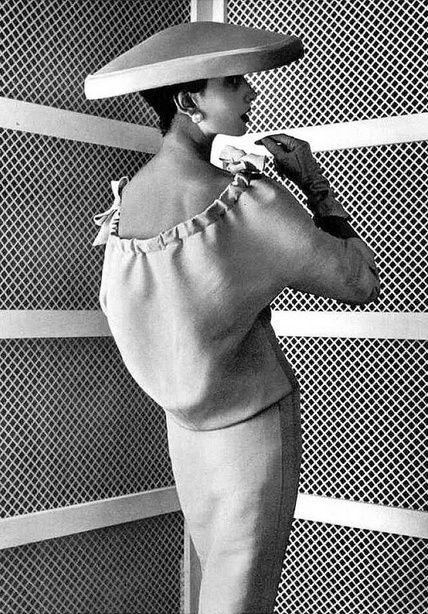

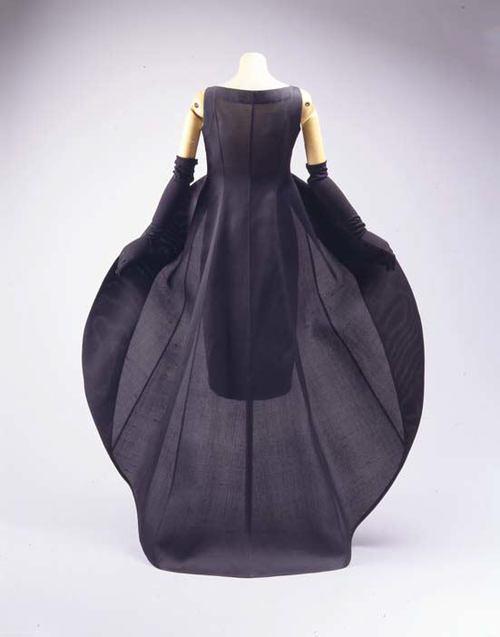

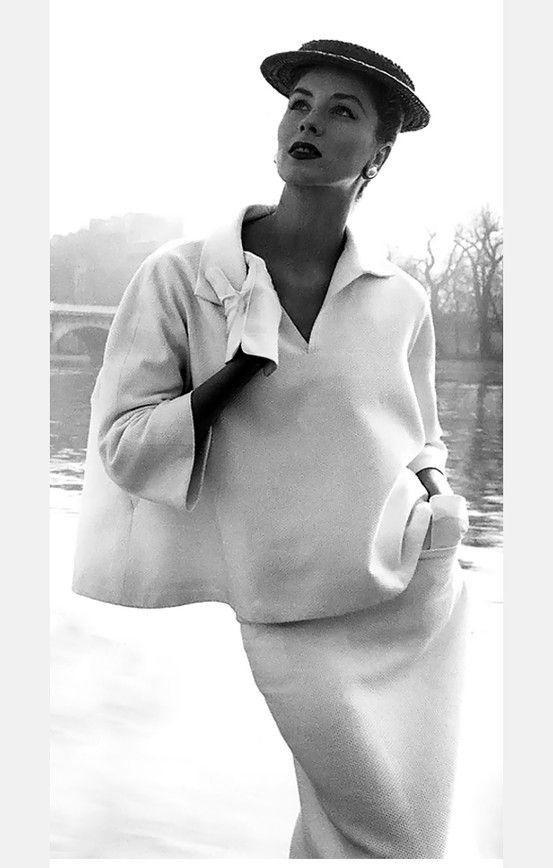

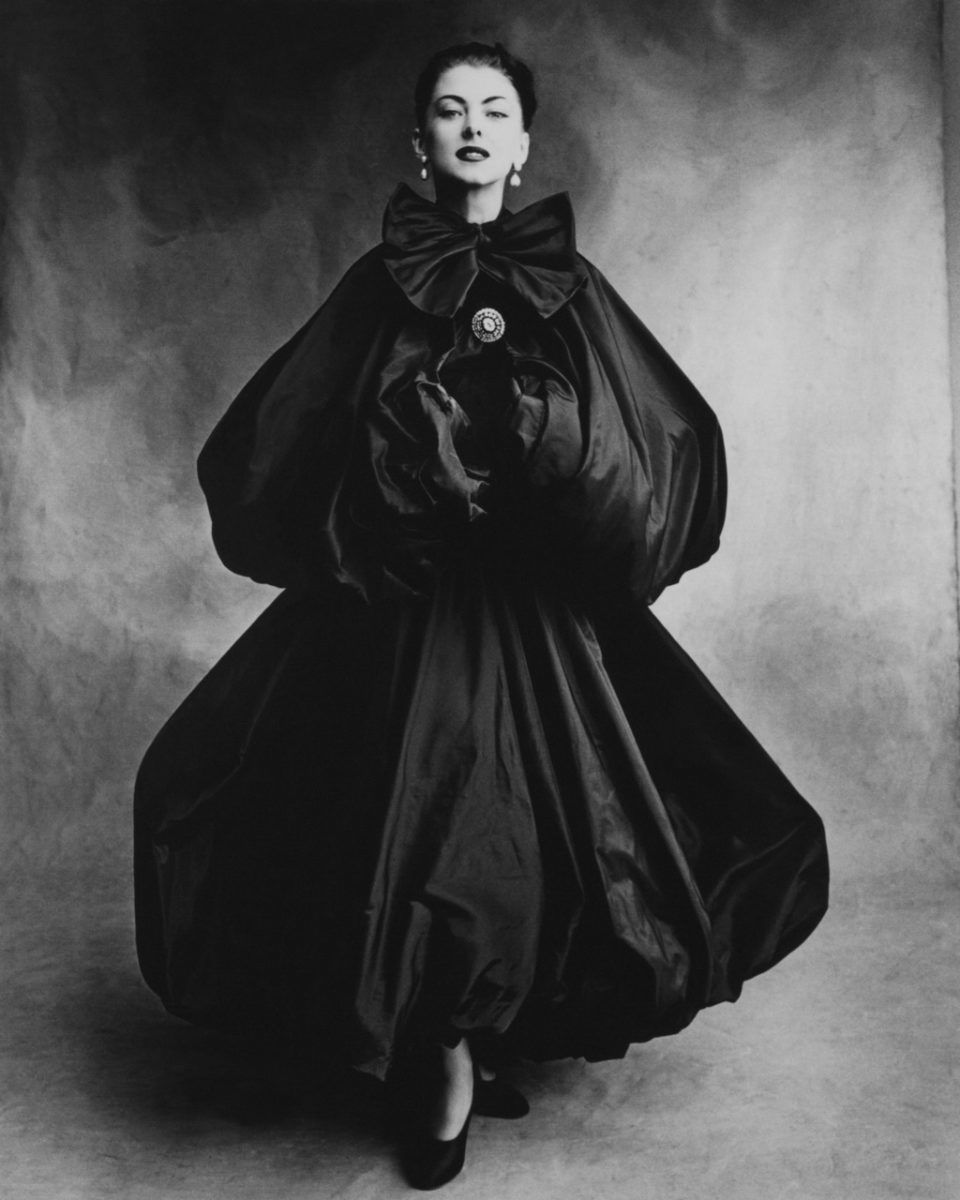

Balenciaga is credited with revolutionizing the female silhouette, with in fact creating a new one altogether. We have Balenciaga to thank, this museum makes clear, for perennially relevant items like the balloon skirt, sack dress and cocoon coat—all now-classic cuts that ignore the natural female shape yet drape on it exquisitely. The pieces of clothing he created, propped behind glass and bathed in the subtlest reverential light, were delicious. They still look modern even though they are many decades old.

I loved looking at these pieces. I loved to imagine wearing them. Balenciaga’s creations are especially attractive to someone like me, a moderately feminine woman uninterested in the brazen accentuating of her feminine assets. The structured collars, raised to hover slightly above the shoulders instead of on them, for example, imbue the neck with a gracefulness it may not have possessed on its own.

I don’t, however, concede that walking the galleries, coveting the items held within them, qualifies as some kind of cultural betterment for me, hushed museum or not. I tend to believe that fashion gets too much attention in our contemporary times, even as I scroll through The Sartorialist on the regular, coveting, appropriating, gazing. Fashion can be fun, and fashion can tell us something about the present time or times past, but fashion can also be cruel, and elitist, and endlessly superficial. Placing it in a museum doesn’t change this, or turn it into one of the humanities.

Neither do forcefully intelligent project like the documentary recently produced by British Vogue and narrated by fashion It Girl Alexa Chung, in which frustration is continually expressed over the lack of seriousness with which most people consider fashion. They almost have me convinced, Chung and the Vogue staffers, until I think about the people I know in my own life who are most concerned with fashion. They are not, it has to be said, the most serious of people, and they wouldn’t tend to take a scholarly approach to clothing.

Those who do take a scholarly approach point to Balenciaga as a progressive, thrusting women ahead into modernity. But let’s not forget that even as Balenciaga pushed the boundaries of what we understand to be an attractive female silhouette, he remained a white man telling women what to wear.

Very rich women, I would add. The Balenciaga Museum makes a point of including the history of each piece’s owner and wearer. The likes of Bunny Mellon and the socialite Mona Bismark (at one time married to the richest man in America) appear frequently. In this museum and others of its genre, the fashion of the masses rarely makes the cut. Instead, visitors ogle items they could never afford. You’ll note that you’ve never seen an exhibition of J. Crew designs in a museum setting. A Balenciaga dress today typically costs between $1,300 and $2,500 (some are more). There are millionaires who feel unable to stomach such price tags. This weakens the argument that fashion in museums tells us something about the way people live. It tells us more about how one tiny swath of a culture lives or has lived, or about our own unrequited aspirations.

As anyone who has studied the topic even briefly knows, aspiration, and its more contemporary relative, “aspirational,” are words that factor often into the world of fashion. Vogue explicitly defines itself largely by providing an aspirational experience to its readers. Outside of editorial, “aspirational” is also a central concept in fashion marketing, of which these museums and exhibitions can be seen as particularly elaborate, tactile examples. The fashion houses themselves often fund them. The best marketing feels like something authentic; if it has a scholarly air about it, all the better. Museum exhibitions, presented with the convoluted language of a gallery catalog, check every box, including the one in which we are tricked into thinking they are something other than marketing.

These were the things I thought about as I walked through the Balenciaga Museum, which I enjoyed very much, allowing myself to feel cultured even through the fog of my cynicism. After, I walked into the old town, had a glass of that local wine, and like a proper commoner made my way back to the main road and the bus stop. I was wearing $100 jeans and Converse.