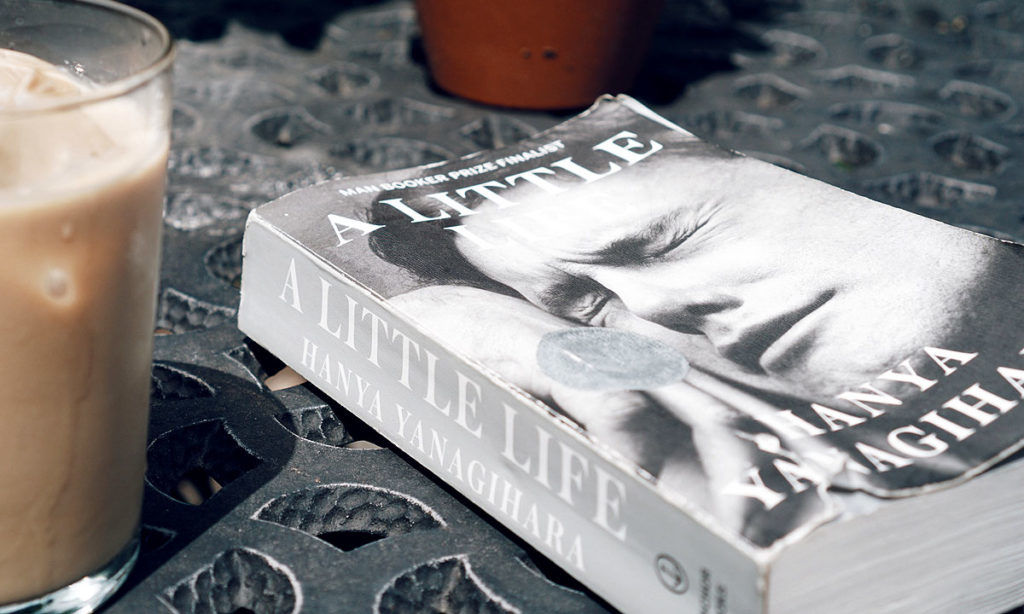

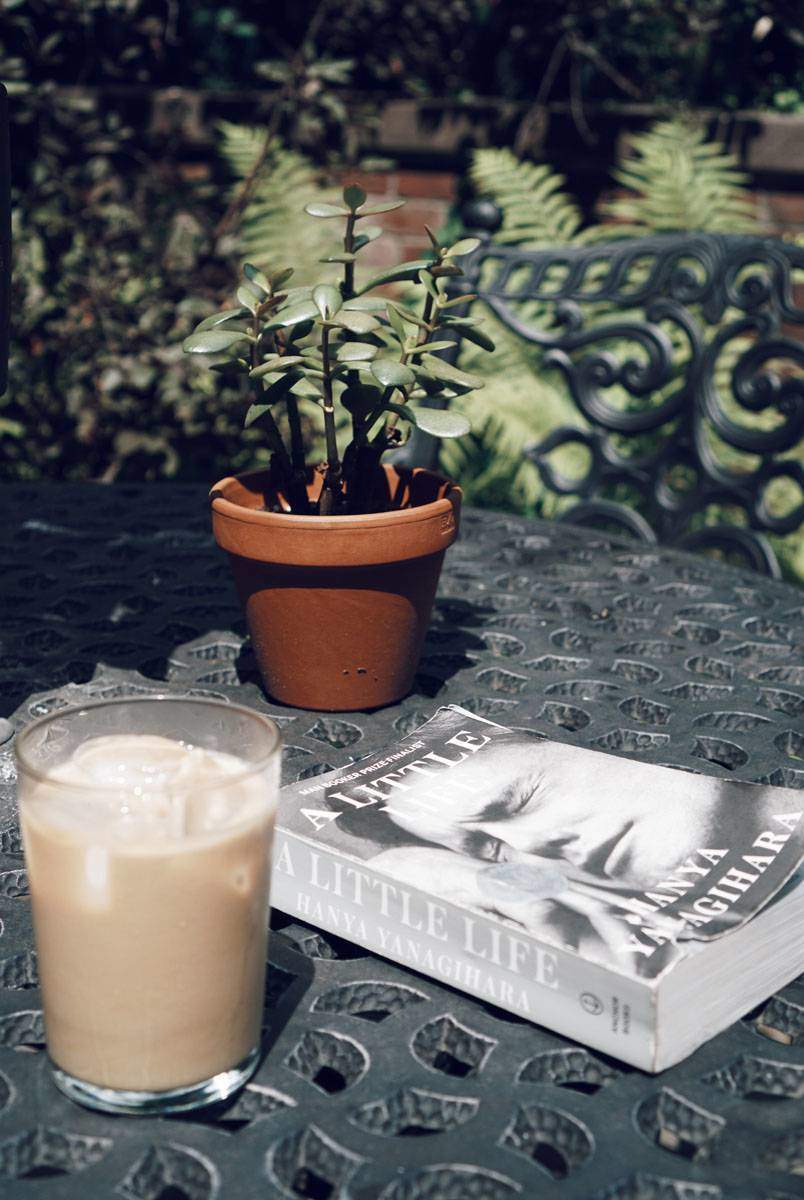

For a book whose very title indicates the prominence of a single character, it took me by surprise to find that 100 or so pages into Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, I still couldn’t remember which main character was which. There are four of them, all men, all with the same formal, bygone manner of speech: Malcom, JB, Jude, and Willem. They all went to an unnamed elite New England college together, where they became the best of friends, then eventually moved to New York City to grow into their adult lives. Yanagihara places us inside all of their heads in one chapter or another, but always from a third-person perspective, causing the reader to conflate all their inner lives into one generalized character. It’s worth noting that the blame for this might fall entirely on my ruined attention span in this technological nirvana we’re living in, and I concede that if your iPhone hasn’t yet stunted your ability to sustain a narrative, those first 100 pages might go differently for you.

The good news is that after this initial stretch, I got it all straight, the mental sludge cleared up, and I started to enjoy the book, which ultimately was not the same thing as deciding it’s a great book.

Out of the group of four, Jude emerges as the true central character, the bearer of the “little life,” with a past so bleak that Yanagihara initially withholds it from the reader, hinting at it and then dishing it out only in small increments as the narrative progresses. This feels by turns like a clever plot device and a cheap ploy—sometimes it’s as if she’s dangling the salacious details in front of us because otherwise she can’t keep us reading all these 814 pages. And there are so many of these details: Jude was discovered as a baby discarded in a trash bag. Jude was abused both physically and sexually by the monks who took him in. Things got much, much worse when one of the monks runs away from the monastery, taking Jude with him. And again, things get much, much worse from there, repeatedly.

That past haunts him into his adult life, leaving him with scars both physical and psychological that he cannot overcome. Miraculously, this does not stop Jude from going to a top law school and becoming a wildly successful attorney in Manhattan. Equally miraculous: All three of his best friends reach the height of success in their chosen fields, as well, even though those fields are creative ones; JB as an artist, Malcom an architect, and the hardest to accept, Willem, who becomes not only a successful working actor, but an A-list movie star. Even their extended circle of friends is comprised entirely of people destined for unlikely success.

And then there are their reactions to it, or lack thereof. That none of Willem’s friends react to his overnight fame is just silly. That Willem himself barely notices it borders on ludicrous. That none of the four men seem to find any joy in their success makes the whole thing tedious. JB describes “the suffocating ennui of being successful,” while I roll my eyes at him. Don’t they know that New York City is littered with smart people who went to good colleges who still only achieved a little bit of success, or none at all?

Speaking of the city they live in, their unlikely stories take place against the backdrop of a present-day New York City that doesn’t line up with the one I know so well as a resident for over 15 years. As other critics have noted, the New York City in A Little Life exists outside of time. We seem to be floating through a perpetual present-day, even as the characters age from college students to men in their fifties. There is no 9/11, no AIDS crisis, even though most of the characters engage in man-on-man action at least some of the time. There is no rise of Brooklyn, and in fact all four young men move straight to Manhattan, even though no young creative men move straight to Manhattan anymore.

Because Yanagihara declines to place the plot within any concrete era, the New York these characters inhabit is a distant one. It may as well be that New York street in the Hollywood studio lot way over in LA, where also 9/11 and the AIDS crisis and Brooklyn have never happened. Jude takes walks from his downtown home to the Upper East Side, and yet during them the city does not breathe the way it does during the walks in, say, Teju Cole’s Open City. We know we are in New York City because places here are occasionally pointed out by name, not because there is any quintessential New York experience brought to life in the book. When the characters are placed in specific locations, those places are described with the flatness of a Powerpoint slide, like in the following passage:

[Jude and Willem meet] at a tiny, very expensive sushi restaurant near his office on Fifty-sixth Street. The restaurant has only six seats, all at a wide, velvety Cyprus counter, and for the three hours they spend there, they are the only patrons.

Add to the lack of verve in that writing the fact that this restaurant seems made up. I worked on 56th Street for two years not too long ago, and while maybe there was at some point such a restaurant along that stretch of Midtown, I never knew about it. More likely, Yanagihara watched Jiro Dreams of Sushi just before writing that passage and relocated it to New York. With all the strange, exuberant restaurants one really can visit in Manhattan, I find it hard to justify making one up, and such an uninteresting one, at that.

This flattened background gives rise to similarly unchanging people, who are not given to evolving. Furthermore, while they are all very different, there is a particular sameness to all of the main characters circling Jude: They are unbelievably caring, especially for Jude. And there is a sameness to most of the minor characters: They are all unbelievably cruel, especially toward Jude. Nowhere do we get to account for the fact that in life most people are far too disinterested and/or self-involved to be either this kind or this cruel.

Later in the book, out of nowhere, Willem and Jude become a couple. It’s a major plot point but I don’t have anything else to say about it. Willem, who is by then very, very famous, doesn’t even try to manage the publicity around his now dating a man, when he has always before dated women. It’s not the move itself, but the nonchalance of his making it, that I found preposterous.

By the time that Willem dies suddenly in a car crash, leaving Jude to even more misery, my reaction became physical: I set the book down in my lap with a slap and yelped, “Oh come on.” Refusing to offer easy redemption is one thing, but this kind of piling on of suffering reads more like a resentment of the very idea of redemption.

I in fact almost missed the car wreck passage, which comes on the last page of a chapter and lasts a mere two paragraphs. By this point, I’d taken to skimming the pages for the major plot points, my interest in the unrestrained prose and in the suffering long since departed, but my desire to know how it all pans out keeping me going.

Yanagihara has said that she intended to create an allegory, not a story completely rooted in reality. The thing about allegories, though, is that they are by definition supposed get at a deeper moral truth, and I am hard-pressed to glean one here. This isn’t an allegory, but it is a novel that would have done better with half the pages and twice the believability.