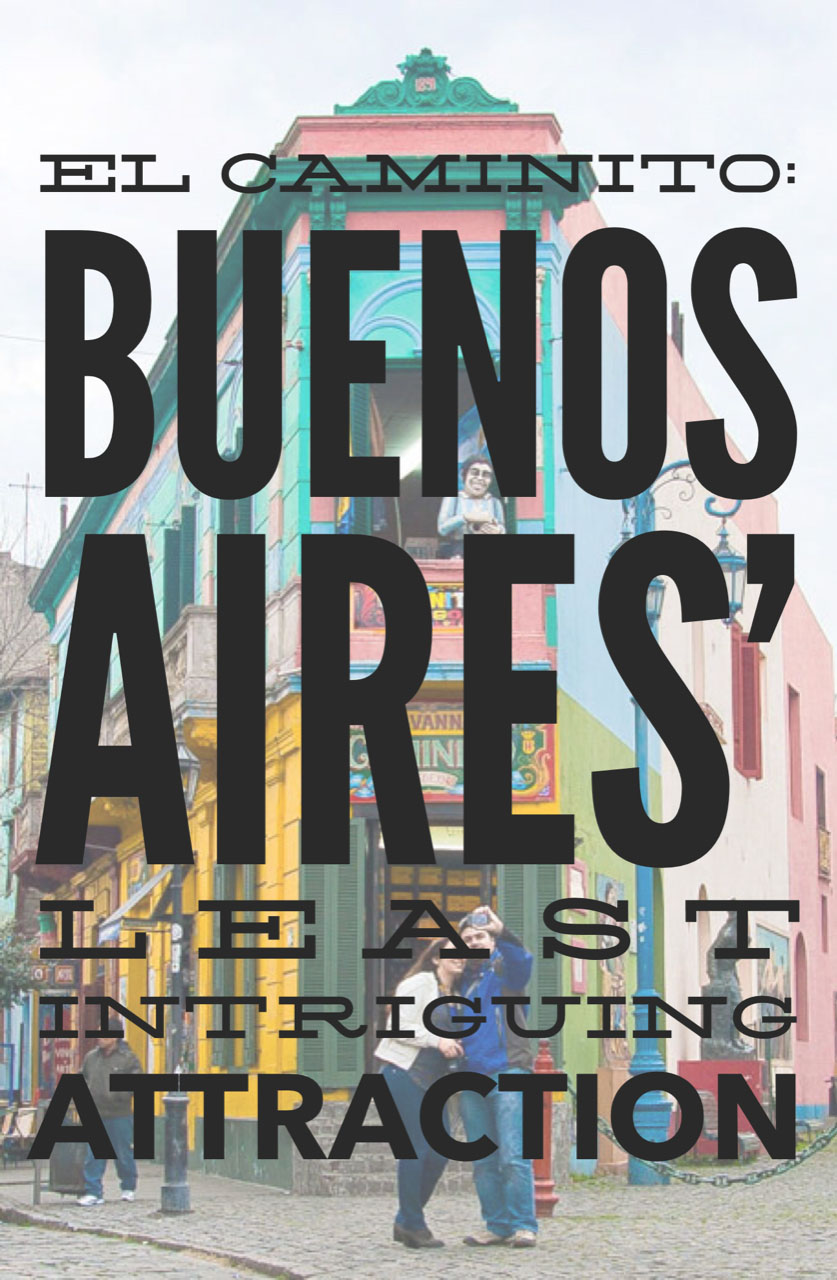

Every guide to Buenos Aires, and I mean every guide, recommends a visit to El Caminito in La Boca. Many of them even feature the colorful street on their covers, despite an afternoon spent there being the surest way to avoid anything real about culture in Buenos Aires. El Caminito isn’t Buenos Aires; it’s Buenos Aires tourism.

Nobody lives in these colorful buildings. The clothing lines are there for effect only. The street itself is a former dump, literally. This is not a once culturally relevant street that succumbed gradually to tourist kitsch; it was built that way from the start, in the late 1950s, by the famous porteno painter Benito Quinquela Martín, who found this abandoned street and used it to create a technicolor version of what his native neighborhood looked like 100 years ago. If your FOMO means you must see El Caminito for yourself, approach it with this in mind, as an art installation. And then, if you can, explore some of La Boca beyond this most obvious tourist draw.

The real La Boca is a neighborhood that hugs the former port that welcomed millions of immigrants from Europe in the 19th century. Many of those immigrants, Italians especially, settled right there, creating a dense, lively barrio of struggle and ambition. In the ensuing decades, it never gained a foothold on wealth and today it remains a poor neighborhood, albeit one that looms large in the country’s popular imagination.

Eight years ago, a friend and I spent one late night that melted into early morning wandering the streets of La Boca, charming examples, all of them, of how not to conduct urban planning. Building owners, made responsible for building and maintaining their own front sidewalks, construct them without any regard to whether they line up well with the street, much less with the sidewalks abutting them. There’s a historical element to the raised sidewalks—they were built that way to combat frequent floods, apparently. At any rate, they result in the need to climb onto some, then down onto others. It’s not so much a walk down the street as it is an obstacle course.

Despite continued warnings that La Boca is unsafe, I never felt a sense of danger that morning, and in fact encountered friendliness at every turn. During our wander, two policemen, after kicking us out of the soccer stadium, invited us into the police station for some yerba matte. We had a late-morning beer at a sidewalk café. We wandered through a park. (We also had tea with Vincent Gallo, which, as one of the more surreal moments of my life and one other visitors are unlikely to repeat, doesn’t really qualify as more than an aside here.)

Back on El Caminito, tango dancers purport to provide another foray into Buenos Aires culture. Going to see tango in Buenos Aires resembles going to see jazz in New York City—an art form enshrined in the city’s historical fabric, but these days relegated mostly to a handful of tourist-friendly dinner clubs, the elite music schools of the city, and the street performers that come out of them. In other words, jazz is not what the kids in Brooklyn are getting up to on Saturday nights in the 21st century. Tango is great, but it’s also a relic. I recommend seeing tango when you’re in Buenos Aires, but I also recommend understanding that doing so is more history lesson than it is immersion in contemporary Argentina.

During my own visit to El Caminito, I sat down for lunch with my then-boyfriend. We sat on a terrace, then watched as a female dog in heat pranced down the street, trailed by a bevy of worked up male dogs. It was the closest to experiencing local culture we would come on that particular afternoon.